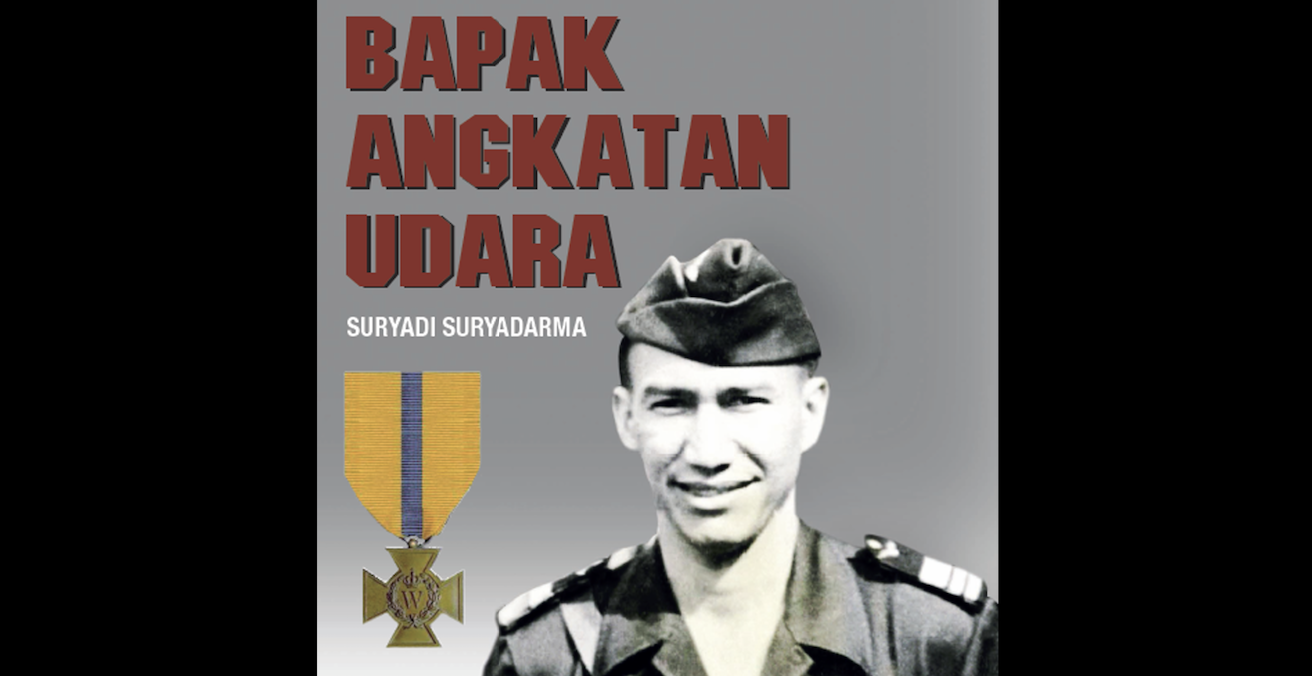

Reading Room: Biography of Indonesian Air Marshall Suryadi Suryadarma

In Bapak Angkatan Udara: Suryadi Suryadarma, Adityawarman Suryadarma gives a biographical account of his father’s life and career as the founder of Indonesia’s air force.

Air Marshal Suryadi Suryadarma was the inaugural chief of the Indonesian air force and held the post from December 1945 to January 1962. The biography was written by his son and is obviously sympathetic to his legacy, but it is nevertheless a reminder of Suryadarma’s contribution to creating the air force and his place in Indonesian history.

Suryadarma was born in 1912. His mother died giving birth and his father died four years later. Both were the offspring of minor branches of Javanese royalty. Subsequently, Suryadarma’s upbringing and education were funded by his grandfather, a medical doctor. His heritage also allowed him to become one of only 21 Indonesians to graduate from the Netherlands military academy at Breda in the interwar years. He graduated in 1934 and was posted to an infantry battalion in Magelang in Central Java.

Having a deep interest in aviation, he chose to join the army because the air force was a branch of the Indonesian army at the time. He learned to fly but for political reasons was not allowed to graduate and was trained as a navigator/observer instead. He was awarded a Bronze Star for participating in a “forlorn hope” attack on warships supporting the Japanese invasion of the small island of Tarakan of the coast of Borneo in 1942. Two of the three obsolete twin-engine Glenn Martin bombers that took part in the attack were shot down. The pilot of Suryadarma’s aircraft was shot in the thigh but managed to land the plane safely despite having had one engine shot out.

During the war, Suryadarma joined the Japanese police force in Bandung but remained sympathetic to the nationalist movement and helped its members who were detained or needing assistance. After the surrender of Japan, he joined the independence movement and was soon drafted to headquarters in Yogjakarta and given responsibility for, amongst other duties, establishing an air force.

As chief of the air force, Suryadarma was involved in two major controversies that characterised his tenure. The first was during the Indonesian Republic’s struggle for independence from the Dutch. During the second Dutch “Police Action” of military aggression against the Republic (Agresi Militer Belanda II), Suryadarma chose to stay with the Sukarno government in Yogjarkarta rather than joining the guerrilla forces to fight.

In early December 1948, President Sukarno nominated Suryadarma and others to join him on a trip to India that was due to leave Yogjakarta by air on 16 December. Consequently, on 15 December, Suryadarma appointed another officer to act as chief of the air force during his absence. The trip was delayed when the Indian aircraft sent to take them to India was stranded in Singapore awaiting flight clearance. The trip was then forestalled in the early hours of 19 December when Dutch paratroopers captured the Yogjakarta airfield and launched their second offensive.

In the hours between the Dutch launching their offensive and Dutch forces reaching the government offices in Yogjakarta, a debate occurred about whether Sukarno and his colleagues should withdraw with the army leadership or stay put and await further developments. The military chief, General Sudirman, chose to retreat with his army to fight another day in accordance with plans anticipating the Dutch action. However, Suryadarma, having surrendered temporary command to another officer in anticipation of the visit to India, decided to stay with Sukarno. Neither Sukarno nor Sudirman appear to have disagreed with Suryadarma’s decision and, having been chief of staff of the armed forces for six months in 1948, he was well placed to advise the president on military matters in Sudirman’s absence.

His choice had no practical significance as he was separated from Sukarno after capture and the air force had little capacity to influence events, but it did weaken the revolutionary legacy of the air force. Nevertheless, it had no impact on Suryadarma’s career as he was reconfirmed as air force chief once the presidential party was released from detention, despite the temporary incumbent staking a claim to retain the post. Consequently, Suryadarma became an unwavering Sukarnoist.

The second major controversy of Suryadarma’s tenure involved the air forces’ failure to provide air cover for a raid into Dutch New Guinea in 1962, which led to the sinking of a patrol boat with the deputy chief of the navy on board. On 15 January 1962, Dutch naval and air forces intercepted three Indonesian navy patrol boats intending to insert a team of army infiltrators from Aru Island into Dutch New Guinea at Kaimana. Two boats withdrew but the third with the deputy chief of navy aboard continued on and was sunk.

The army and navy blamed the sinking on the failure of the air force to provide cover. Suryadarma claimed not to have been aware of the operation and was not involved in the planning. Consequently, no provision was made to deploy aircraft or provide air cover for the operation. Part of the problem was that Sukarno had encouraged inter-service rivalry to constrain the political power of the army so that there were no effective joint or operational command arrangements. Flowing from that rivalry, and excessive secrecy, the air force had been excluded from the planning and execution of the operation.

Politically, Sukarno had no option but to dismiss Suryadarma, which he did a few days later on 19 January 1962. Nevertheless, Suryadarma held minor cabinet posts under Sukarno until he was briefly detained after an attempted coup inspired by the PKI (Indonesian Communist Party) in October 1965. Following this, Suryadarma soon faded into history and died in 1975. Despite the political and economic constraints that hobbled the development of Indonesia’s air force, Suryadarma left an enduring legacy as its founding father.

The book is worth reading but contains some contentious claims that need further supporting evidence and explication. For example, it is claimed the mission Suryadarma was part of in 1942 sank a Japanese cruiser and destroyer. There is no evidence to support this claim. Another example is the claim that Suryadarma had imbibed the apolitical military ethos at Breda and held fast to it during his military career. That was impossible during the early days of the Republic, especially after President Sukarno seized authoritarian powers in the late 1950s. By choosing to side with Sukarno, rather than General Nasution and the army, Suryadarma and the air force became actors in the political drama that unfolded in the 1960s.

Adityawarman Suryadarma, Bapak Angkatan Udara: Suryadi Suryadarma, (Jakarta: Kompas, 2017). The book is published in Bahasa Indonesia.

Robert Lowry retired from the Australian Army as a lieutenant colonel in 1993 and has since worked and studied in the field of military politics and reform in Indonesia, East Timor and Fiji. He is the author of The Armed Forces of Indonesia (1996) and Fortress Fiji: Holding the Line in the Pacific War, 1939-45 (2006). He is also a former president of AIIA ACT.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.