Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Turkey, Idlib, and the Syrian Civil War

The Syrian Civil War has been a turning point in Turkey’s policy towards its region. Ankara increasingly finds it hard to pursue “multilateralism” to realise its foreign policy goals.

The violent civil war in Syria has devastated much of the country since 2011. According to UNHCR, in only Idlib, a troubled region in northwest Syria, more than 900,000 people are estimated to have fled their homes in recent months. Turkey, home to nearly four million Syrian refuges, decided to open its borders to Europe for refugees and called NATO for consultations after more than 30 of its soldiers were killed in Russian-backed Syrian government airstrikes on one single day, February 28, in the Idlib region. Recently escalating developments raised many questions about the future of unsuccessful multilateral efforts to find a solution to the crises in Syria that have persisted since 2011, including prospects of an already fragile Turkish-Russian “partnership” in Idlib, the fate of the 2016 Turkey-EU refugee deal, and the worsening humanitarian situation of refugees heading to Europe.

Back to the future in Turkish foreign policy towards the region

Turkish foreign policy has been built on the main principle of “peace at home, peace in the world,” initiated by the founder of the Turkish Republic, Kemal Atatürk. Acknowledging its location close to, if not at the centre, of instability and crisis zones of the Middle East, Ankara always “had to” cautiously chose its foreign policy instruments under “fragile” regional developments. Since the Cold War era, Turkey struggled to find a workable “balance” between its relations with the West and its relations with neighbours in the region, due to the successive Iraq-Iran crises and especially the post-2011 Syrian developments.

Turkey “chose” to intervene with military force after its efforts to create a no-fly zone and launch a multilateral intervention were not realised by the international community. Ankara justified its use of military force both with mixed humanitarian motives in relation to Syrian refugees and with national security concerns, like ISIS and particularly the YPG, the Syrian Kurdish forces of the PKK-affiliated Peoples’ Protection Units. Following both Russia and Iran entry into Syria in 2015 with their own armies, rivalry and power politics further complicated the already unstable regional confrontation among actors.

Turkish-Russian Cooperation under the Clout of Idlib

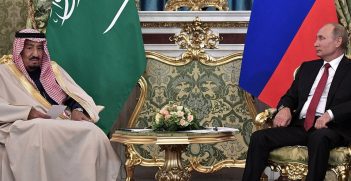

The post-2016 period in Syria coincides with an increase in cooperation between Turkey and Russia across several sectors, including the Turkstream natural gas pipeline and the delivery of a Russian S-400 air and missile defence system in a time when US support for the YPG has resulted in discontent in Turkey vis-a-vis both the U.S. and NATO. Cooperation with Russia enables Ankara to maintain a certain level of autonomy in its relations with its NATO allies, as well as the opportunity to display an “alternative” to the West.

Although Russia and Turkey began to cooperate in Syria through the Astana talks initiated in 2017 to coordinate a joint ceasefire plan, two countries supported two radically different solutions of the conflict in general, and in Idlib specifically. Turkey has been primarily driven by countering the YPG’s increasing influence, with its spillovers in Turkey, as well as establishing of a safe zone to resettle refugees. Russia, on the other hand, supports the Assad regime, aims to include the YPG in the peace process, and is working to eliminate terrorist activities. Turkey criticised the Assad regime for the deepening humanitarian tragedy as it has bombed civilians, while Russia criticised Turkey for not preventing terrorist activities. Intensifying conflict reached its peak in the February 2020 airsitrikes on Turkish troops, killing more than 50 soldiers in one month.

Last week a military “ceasefire” has taken effect in Idlib, after extensive talks between Erdogan and Putin, who agreed on a “descalation area” and “joint patrols.” Yet there is little likelihood that this will turn into a permanent peace as Turkish and Russian goals in Idlib seem irreconcilable.

Conclusion

Although Turkey’s potential in regional issues could still be observed in some cases, such as its taking part in the Astana peace settlement process, Turkey seems to have become entrapped between a rock and a hard place in the Syrian Civil War by becoming a party to many rivalries and confrontations of regional and outside actors. It also faces the challenge of “legitimising” its actions between mixed motives of humanitarian and national security concerns as a country left alone by its Western allies to carry all the humanitarian costs. Considering its disagreements with Iran and Russia over the downfall of Assad and its difference in opinions with its major Western ally, the USA, regarding the pursuit of strategies toward Syria, Ankara is either left alone or had to become a party to the power struggle between Russia, Iran, the USA, and the EU over Syria.

All in all, Turkey’s immediate call for NATO consultations and opening of its borders to Europe for refugees demonstrates once again Turkey’s efforts to put the crisis into the international agenda. This policy not only aims at pushing West to act on the worsening refugees problem, but also to push the EU to put more pressure on Russia for a deal in Syria. Therefore, Iblid has the potential to test the limits of Ankara’s long-standing regional efforts to find a workable “balance” between its relation with that of regional states and the West.

Gonca Oguz Gok is an associate professor of international relations at Marmara University in Istanbul, Turkey.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.