South China Morning Post reported Aug. 14 that China’s Agricultural Cultivation Bureau under the Ministry of Agriculture had taken control of around 1,700 farms and 3,200 agricultural companies in sectors that include seed distribution, dairy production and rubber cultivation. This followed several similar consolidations of smaller businesses into state-owned enterprises, including the China National Cereals, Oils and Foodstuffs Corp. and Beidahuang Kenfeng Seed Co., to promote large-scale agribusiness. These efforts highlight Beijing’s ongoing strategy to move toward agricultural modernization and implement rural reforms to fulfill its fundamental imperative to maintain food security for its massive population.

Beijing Moves to Consolidate Agricultural Sector

Summary

Analysis

The progress made by the Ministry of Agriculture and these two state-owned enterprises go hand-in-hand with a broader shift in Beijing’s agricultural strategy. In recent years, the national government has encouraged the transformation from a traditional system of household farming dominated by small-scale cultivation toward the development of large-scale farms. This is meant to facilitate specialized, intensive and industrial-scale operations. Although the transition is still in the early stages, once fully realized it would allow state-owned companies to better integrate domestic resources and better secure available food.

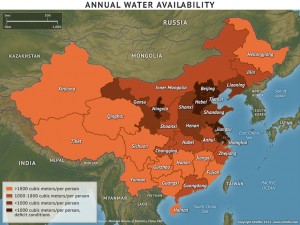

To achieve food security, China must feed its large population using its comparatively limited arable land and water resources. The difficulty of maintaining production is compounded by the growing demand for grain that accompanies accelerated urbanization, a growing middle class and spreading industrialization. These transformations have already brought the country’s annual grain consumption per capita to an average of 445 kilograms (981 pounds) — more than twice what it was three decades ago. This is expected to reach more than 500 kilograms by 2030. At the same time, small-scale agriculture and land ownership are important resources that sustain China’s agricultural population, despite their low productivity and efficiency.

Although historically prone to food shortages, China has not experienced one since Beijing implemented rural reforms in the 1980s. But the past decade has led to a number of changes that have stressed the agricultural sector. Domestic consumption has grown as large portions of the rural population have migrated to cities and no longer rely on cultivation for their livelihoods. The actual amount of arable land has also been reduced because of water usage and widespread soil deterioration across an area some estimate to total to the size of Belgium. The combination of these factors has led to questions as to the viability of China’s self-sufficiency strategy and, ultimately, the nation’s food security.

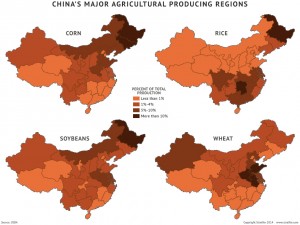

China’s total grain production reached a record 601 million tons in 2013, continuing an eight-year growth trend. However, high production was accompanied by a surge in grain imports to 72 million tons — equating to more than 10 percent of annual domestic production. Soybeans have been one of the top imported staple crops since the early 2000s; currently, soybean imports account for 80 percent of domestic consumption. China also ceased to be a net exporter of corn in 2010; the amount of imported corn rose to seven million tons in 2013, or around 8 percent of its domestic consumption. If this trend continues, China will become the world’s top corn importer by 2019. Soybeans and corn are primarily used as feed for livestock, an indication of growing meat consumption nationwide as the middle class grows. However, rice and wheat, primarily consumed by the population directly, have also grown substantially in the past two years, although China remains self-sufficient in these two crops and current imports comprise less than 1 percent of domestic consumption.

Chinese agricultural imports will continue to rise in the near-term. In order to meet its long-term needs, Beijing will need to increase efficiency and productivity in the domestic agriculture sector to mitigate the effects of depending on foreign production. Meanwhile, the broader transformation of rural areas would facilitate a shift toward agribusiness and mechanization through consolidation. Ultimately, the focus on large-scale farming without undermining stability could gradually help Beijing improve agricultural yields and more readily incorporate efficient technology to bolster food security.