Risks, Opportunities and a new Gas Pipeline in Central Asia

The long-awaited gas pipeline connecting Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India is finally underway. What role can Australia play?

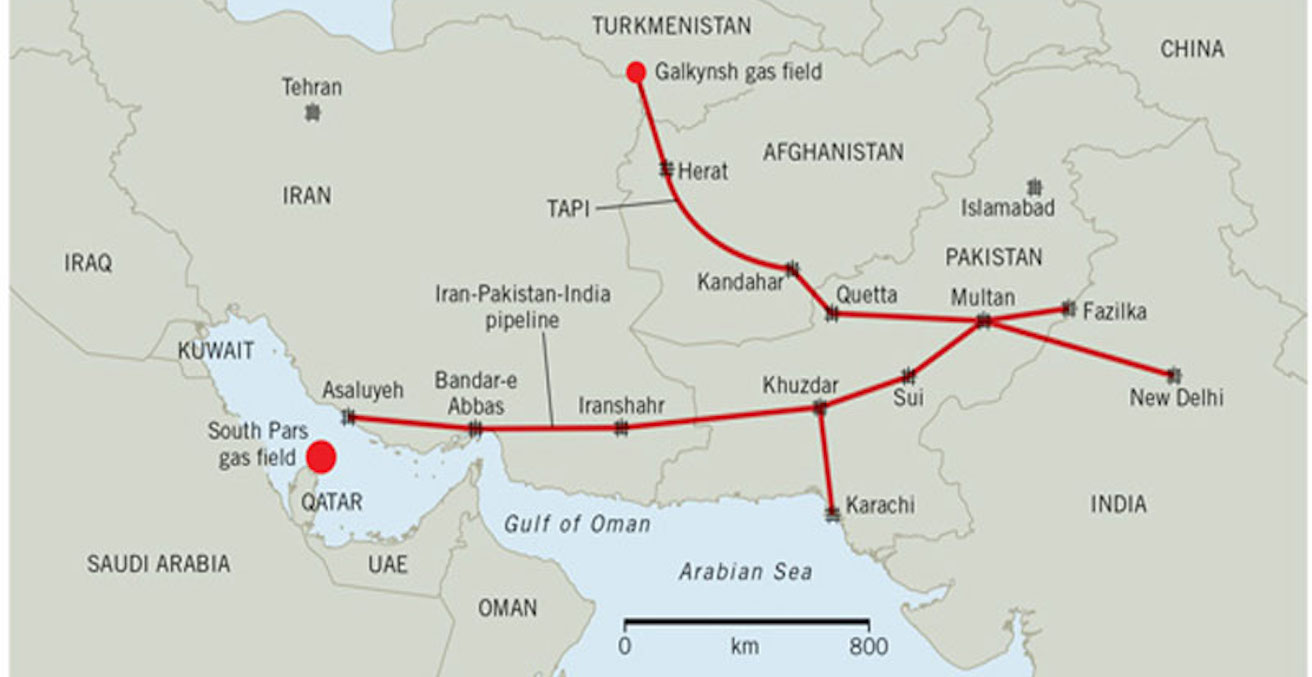

Last month the construction of the Afghan section of the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline officially began through an opening ceremony near the town of Serhetabat, Turkmenistan. The TAPI is expected to be completed in 2020 and will carry 33 billion cubic metres of gas from the Galkynysh fields in Turkmenistan to Herat, Nimruz and Kandahar in Afghanistan, and continue on to Quetta, Dera Ghazi Khan and Multan in Pakistan before culminating at the Indian border town of Fazilka.

Supported by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the 1600-kilometre USD$10 billion (AUD$13 billion) pipeline is the largest multilateral energy project undertaken in South Asia and is expected to have far reaching implications in one of the most energy insecure and politically volatile parts of the world.

While Australia’s interest in the region has been confined to bilateral relationships—the highlight of which is the growing trade, security and maritime cooperation with India—projects such as the TAPI can be used by Canberra to envision a more integrated policy towards South Asia. Using our considerable knowledge of energy infrastructure to provide technical support to Washington’s integration plans in Central Asia—of which this pipeline is a key component—can be a pragmatic contribution to the America-Australia alliance. It is a contribution that bears much lower risk than acceding to President’s Trump’s recent call to participate in joint naval exercises to confront our main trading partner.

However, the TAPI itself bears considerable political risk, notwithstanding the potential benefits in terms of regional interdependence and peacebuilding. First is the possibility that the historical animosity between India and Pakistan, and Islamabad’s acrimonious relationship with Kabul, could derail the implementation of the project. In interviews with Indian and Pakistani policymakers about the pipeline in 2014, several mentioned that the project would provide rivals with a ‘control button’ on a neighbouring state’s energy supplies, making deliberate disruptions a significant threat. Analysts have contended that frameworks such as the Transit Protocol of the Energy Charter can address such risks.

The detriments of inter-regional rivalry, however, pales in comparison to the threat posed to the pipeline by terrorist and insurgent groups. The TAPI will traverse some of the most restive regions in South Asia, including Herat and Kandahar in Afghanistan, as well as Quetta, the capital of the insurgency-affected southwestern province of Pakistan. The determining factor is the ability of the Afghan government to ensure sustained security of the transmission line in areas controlled by the Taliban.

Ironically, the TAPI was first negotiated between the then Taliban regime and the US in the 1990s, a fact not lost to spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid, who recently stated that his organisation was “ready to protect the TAPI” owing to the group’s historical stake in the project. While such overtures provide little assurance, they create concern about whether the Taliban can benefit from providing security to the project. To safeguard the pipeline from terrorist attacks and ensure that militias do not benefit from the project, the international community may consider further investment in Afghanistan’s fledging security institutions, thereby also contributing to long-term capacity building.

While the security challenges posed by non-state actors is daunting, it could also be argued that the TAPI may create a convergence in the interests of India and Pakistan in having a secure and stable Afghanistan and Baluchistan. For decades these have been platforms for proxy wars and power struggles between Delhi and Islamabad.

While Kabul would undoubtedly benefit from any collaboration between Islamabad and New Delhi on state-building in Afghanistan, such cooperation would also alleviate Turkmenistan’s concerns regarding the spread of extremism from its southeastern borders. US-led efforts to reconstruct Afghanistan, and Australia’s contributions to that effort, will benefit immensely from the exploitation of such interdependencies and mutual security interests.

Beyond the region, Russia and China are likely to be antagonistic towards the TAPI, according to some analysts. However, evidence suggests a more conciliatory and cooperative approach.

The ADB has formally sought Chinese expertise on the technical aspects of the pipeline, and the China National Petroleum Corporation has expressed interest in participating in the project. Unfortunately, this has not been well received by India in the past and such reticence is expected to be further entrenched after the Doklam crisis last year.

On the other hand, Russia’s Gazprom has shown interest in participating in the TAPI, which, along with the involvement of Russian companies in the Central Asia-China pipeline, indicates an exception to Russia’s general opposition to pipelines in Central Asia that bypass its territory. However, Turkmenistan has reportedly opposed Russia’s involvement in the TAPI due to historical animosities, which resulted in a temporary disruption in gas trade between the two countries in 2009.

While significant opportunities exist for the participation of Russia and China in the TAPI, the complex relationship that they share with the member states along the pipeline, as well as their differing yet intense rivalries with the US, might well result in geopolitical conflicts. Managing the geopolitical risks associated with the TAPI and other transnational infrastructure in Asia would require undertaking inclusive cooperation with countries within and beyond the region.

While at this stage, an Australian role in the TAPI seems unlikely, an Indian energy expert provided an interesting insight, which may be reflected on by policymakers in Canberra: “The US’s efforts towards energy integration in South Asia are often not well-received in these countries. If Australia led some of these projects, there is a chance that they may be more widely accepted as Canberra is not seen as a belligerent force”.

In the broader scheme of things, the TAPI is part of America’s New Silk Road, an integration project that aims to connect Central and South Asia through energy and transport infrastructure. Some analysts have pointed towards synergistic opportunities with China’s Belt and Road Initiative, while others have predicted geopolitical clashes.

Policymakers in Canberra should carefully consider Australia’s opportunities in a rapidly unfolding international scenario underpinned by multilateral infrastructure. One option could be working with our allies on infrastructure projects that can contribute to peace and development, while using our middle power status and economic partnerships to alleviate zero-sum perspectives towards Asian integration.

Dr Mirza Sadaqat Huda is a postdoctoral research associate at the Griffith Asia Institute of Griffith University. Previously, he worked as a research analyst at the Sustainable Minerals Institute of the University of Queensland. He has held research appointments in India, Nepal and Bangladesh and undertaken extensive fieldwork in South Asia.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.