Australia’s Credibility on Human Rights Issues

Having a chair at the UN Human Rights Council is a privilege to many countries, and Australia is the first Pacific nation to achieve this goal. However, Australia’s presence at the Council has not been matched by a resolve to eliminate domestic and international human rights abuses.

Australia’s human rights history can be considered contradictory at best. Internationally, Australia championed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and supported the belief that “everyone deserves a fair go,” in the words of the Attorney-General Herbert Vere Evatt in 1949. Domestically, however, the White Australia Policies were still very much a reality in Australia, only ending in the 1970s under the Whitlam government. The Australian government in 1949 reconciled the contradiction between the White Australia Policies and the UDHR by arguing for the supremacy of a nation’s domestic right to determine the appropriate laws for its own people, and these domestic laws being independent to the international treaties that Australia subscribes to.

Since then, Australia has ratified the seven core international human rights treaties, ranging from the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to the Convention on Rights of Peoples with Disabilities. It is also a part of the Universal Periodic Review whereby Australia is accountable to in-depth investigations regarding their compliance with international human rights law. In 2018, Australia was elected to sit on the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) for a three-year term. In the broad sense of respect for human rights, it is easy and commendable to see why Australia, a long-standing democracy that has championed the fundamental rights of the majority of their citizens, achieved a seat on the UNHRC. However, with the ongoing human rights violations that are occurring domestically and Australia’s lack of voice in the international community, it is evident that even having been appointed to the UNHRC, Australia has not lived up to its expectation that as the first democratic Pacific nation to sit within this council, a more robust scrutiny of human rights violations should have been undertaken.

The UNHRC has no legal enforcement mechanisms, so pressure by Australia and other nations could be advantageous in pushing governments that violate human rights to act. Pressure, and the process of naming and shaming gives way for the violations of rights to be public knowledge, leading to a higher likelihood of domestic reform within nations that perpetrate these abuses. Many have urged the Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne to use this platform to voice concerns about countries that have systematically evaded the council’s scrutiny and appeals for the betterment of human rights conditions within said countries. Such instances include the call for Australia to emphasise China’s gross violations of the rights of the Uighur population, whereby approximately one million people have been detained in re-education camps. However, Australia has refrained from making any forthright assertions towards the UNHRC. For a country that prides itself as a promoter of human rights, and in addition to the high standards of living that the country commits to its citizens, the contrast with Australia’s international assertion in this instance is startling.

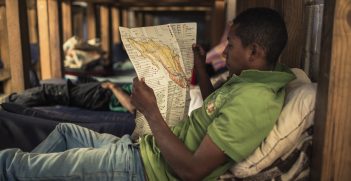

The domestic human rights situation in Australia could be a possible root cause as to why the government has refrained from using its seat on the UNHRC for advocating hard-line stances against other countries. Instead, Australia prefers “constructive bilateral dialogues” with nations over firmer actions like sanctions. This may be because domestically, Australia has not improved its treatment of refugees and asylum seekers and still heavily discriminates against the indigenous population, tying in here with violations of the rights of children. According to the Human Rights Watch Annual Report of 2019, the Australian policy of offshore detention of refugees and asylum seekers is still one of the most inhumane means by which these individuals are processed prior to entering the country. Furthermore, Australian Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander individuals remain highly discriminated against, especially when one looks at the disproportionate incarceration rates of these groups of people. With the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Australian government has further exacerbated the violations of minority rights, as seen in the Queensland governments’ treatment of individuals in youth prisons, where incarcerated children are being detained in harsh and restrictive conditions using the threat of the virus as justification. Notably, 61 percent of these individuals are Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islander children.

The current system of enshrining and protecting rights in Australia is deeply flawed. The absence of a bill of rights in Australia’s constitution limits the Australian government to enacting or rejecting laws that promote human rights. This means that the legislative body, elected by the majority of the population, has the decision-making capacity to respect and promote human rights laws domestically. On the converse, if a domestic regime fails to enact any number of rights protections, it is the legislature that is given the power, on an ad hoc basis, to create these laws and oversee compliance. However, with a majoritarian-elected legislature, the most vulnerable groups tend to be those most likely to be discriminated against. Hence, in putting a majoritarian-elected legislature in charge of promoting minority rights, the two most at-risk groups of peoples in Australia are the Indigenous population and asylum seekers and refugees. The implementation of a statutory bill of rights in Australia would codify in writing the actual rights that Australia seeks to protect and build on domestically. Further, in incorporating the international treaties that Australia has signed, a bill of rights would only improve Australia’s credibility as a human rights protector, as it would be held accountable both domestically and internationally.

This is not to say Australia has completely ignored the importance of human rights. Both internationally and domestically, Australia has promoted liberal democratic rights and supported the multiple international human rights laws. However, as Gareth Evans, one of the founding fathers of the Responsibility to Protect, has noted, “middle powers like Australia occasionally talk the talk,” which when assessing their contribution to the UNHRC, seem to quite heavily fit this mould of “all talk, but no action.” Australia has committed to advancing five campaigns while on the UNHRC – gender equality, good governance, freedom of expression, rights of indigenous peoples, and strong national human rights institutions and capacity building. Looking at Australia’s track record since being on the council, it is easy to point out its successful advocacy on more civil and political rights, such as the abolishment of the death penalty. When it comes to the economic, social, and cultural rights like citizenship and inherent dignities of individuals, however, Australia’s support and promotion has been lacklustre at best.

Campaigning for the seat on the Human Rights Council, Australia projected a willingness to promote and advance the fundamental rights of human beings. While championing this role internationally for the last three years, domestically Australia has fallen short of ensuring these rights are entrusted upon the minority groups such as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and refugees and asylum seekers. To be an active contributor to the progression of international human rights protection, Australia needs to take a serious look inward. Australia needs to evaluate what it can do better domestically as it jumps headfirst into tackling human rights violations elsewhere. Failure to address this hypocrisy could affect Australia’s legitimacy in the human rights space by discrediting the liberal democratic fundamentals that Australia outwardly champions.

Katrina Sukumaran is a final year student undergoing a Double Bachelor’s Degree of International Relations and International Security Studies at the ANU. She is currently an intern at the AIIA National Office.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.