Let them Speak: Australian Values and Chinese Students

If Australia insists that only Chinese student voices critical of the Chinese government are authentic and deserve our support, a majority will be alienated and this would be an affront to Australian values, where all in society have a right to speak up.

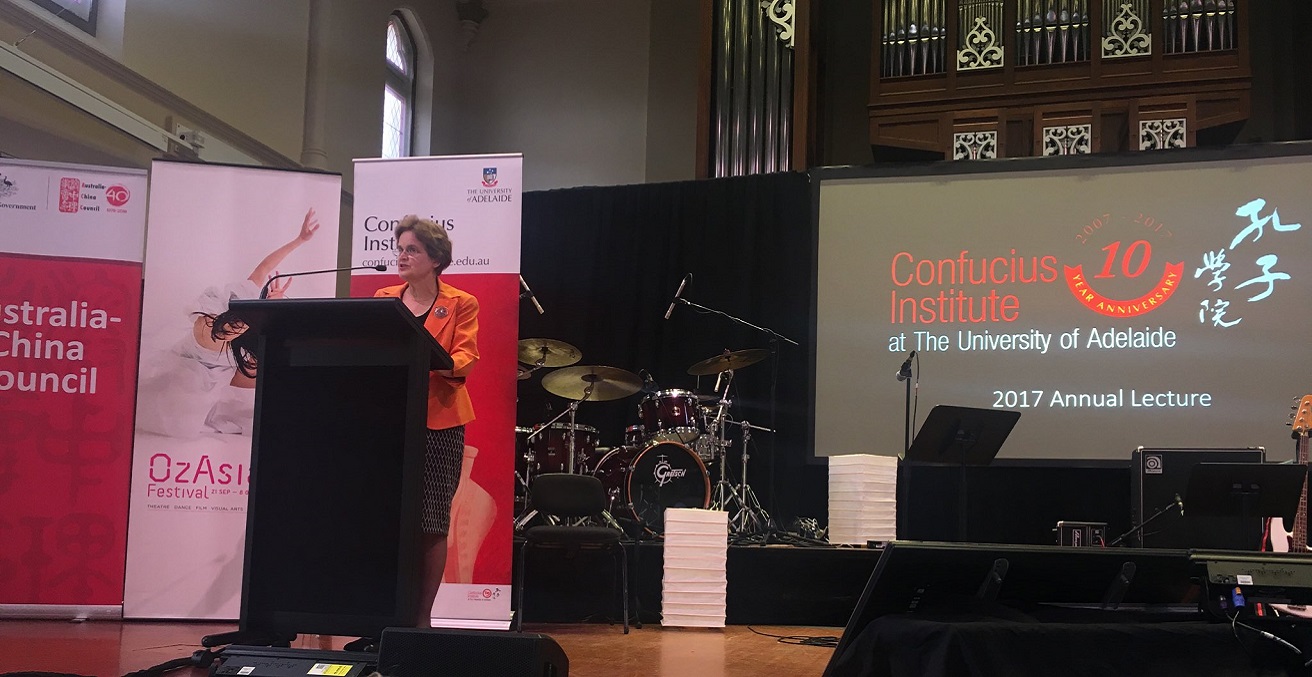

A speech delivered earlier this week by Frances Adamson, Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), at the University of Adelaide’s Confucius Institute has attracted significant media attention.

In reporting on her address, the headline the ABC went with was “DFAT boss warns international students to resist Chinese Communist Party’s ‘untoward’ influence”. The opening paragraph of the national broadcaster’s piece contended that the head of DFAT had asked “students to engage in respectful debate rather than spread propaganda or attempt to gag views they disagree with”.

International media such as The Times followed the ABC’s lead: “Australia’s top diplomat, Frances Adamson, warns Chinese students to respect free speech”.

But here’s what Adamson actually said. After telling Chinese students that Australia was honoured they had chosen to study here, she offered this advice:

We want you to experience our contest of ideas and participate fully in it…No doubt there will be times when you encounter things which to you are unusual, unsettling, or perhaps seem plain wrong…So when you do, let me encourage you not to silently withdraw, or blindly condemn, but to respectfully engage.

The silencing of anyone in our society—from students to lecturers to politicians—is an affront to our values.

There wasn’t a single ‘warning’ to Chinese students in it.

In recent months a number of prominent Australian commentators have depicted close links between the Chinese government and Chinese students, with the former either controlling or intimidating the latter.

In August, former Fairfax China correspondent John Garnaut asserted that Chinese students embody a “racial chauvinism” that Beijing is exporting to Australia’s shores. At a recent higher education summit, he was also reported to have said that the Chinese government is stirring up “red hot patriotism” on Australian university campuses and this posed a potential national security risk. Last month The Australian’s China correspondent Rowan Callick wrote that a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) ideological campaign is behind a “war being waged” by Chinese students against their “politically incorrect” lecturers in Australia.

In June, the ABC’s Four Corners program interviewed Lu Lupin, president of the Chinese Students and Scholars Association at the University of Canberra. When prompted, Lupin said that the Chinese embassy had supported her peers to assemble to welcome visiting Chinese Premier Li Keqiang (with flags, transportation and a lawyer to help liaise with police). She also said that she would tell the Chinese embassy if some students were organising a human rights protest “just to keep all the students safe and to do it for China as well”. Four Corners also spoke to Anthony Chang, a Brisbane student and democracy activist, who said his parents in China had been threatened by state security officials for their son’s Australian activism.

As evidence of the “red hot patriotism” of Chinese students and Chinese government interference in Australian universities, John Garnaut and others have referenced “denunciations of Australian university lecturers who have offended Beijing’s patriotic sensibilities”, such as in August when some Chinese students complained about a University of Sydney lecturer’s use of a map that depicted Chinese-claimed territory as part of India.

But here’s the problem with that logic: the sum total of such incidents this year has been four. Meanwhile, there are 131,203 Chinese students with their heads in the books at more than 30 Australian universities.

Vicki Thomson, the chief executive of the Group of Eight, comprised of Australia’s elite universities, said last month that there was “no evidence” that Chinese government interference was happening in any “broad, widespread way”.

Of course, any untoward foreign government interference is too much and needs to be called out and resisted. But while much media commentary prefers anecdotes, rigorous academic research into Chinese students in Australia goes unmentioned.

Associate Professor Fran Martin, an Australian Research Council Future Fellow at the University of Melbourne has conducted detailed ethnographic research involving regular and wide-ranging conversations with scores of Chinese students in Australia. She says that only two students in her contact group have had any interactions with the Chinese consulate and these two were on Chinese government scholarships. One remarked that because of her scholarship she felt that she needed to occasionally show her face at consular events. But she had not been involved in any political events, nor had she been invited to be involved by any consular officials.

Martin describes how the patriotism exhibited by Chinese students tended to be similar to the loyalty to “one’s family or school, yet not precluding criticism of the government and the Party”. It certainly was not “a straightforward identification with either the CCP or the Chinese state”.

Research by the United States Studies Centre published in May found that Chinese citizens were in fact less nationalistic than those from India and Indonesia. And in scholarly work published last year by Harvard’s Professor of China in World Affairs, Alistair Johnston, survey evidence revealed that “most indicators show a decline in nationalism since around 2009” and that China’s youth are less nationalistic than older generations.

On the impact of Chinese government propaganda, one of Fran Martin’s interviewees said, “To tell the truth, I don’t really believe the Chinese news media”, while another ventured:

I don’t read Chinese newspapers very much because, sometimes I feel the things they write aren’t too meaningful. The point is, right from the start they say how great the country [China] is, and on and on—it’s all so meaningless (wuliao)!

In recent comments, Rongyu Li, deputy vice chancellor of the University of Canberra said that travel and technology meant the “brainwashing” of the past was no longer possible and that the “political agenda (of President Xi) is very different to the agenda of the students and their parents”.

Wanning Sun, professor of media studies and communication at the University of Technology Sydney has also run focus groups with Chinese students this year. Her motivation for doing so was simple: “The best way to get a handle on the sentiments of Chinese students was to actually go and talk to them.”

Sun found a diverse range of opinions on contentious issues within the Chinese student cohort, and sometimes even a deep ambivalence within individuals. She also reported that some Chinese students came to Australia enchanted by the notion that Australia’s media is free, but then when they read the local coverage of China, and about themselves, they were left feeling disillusioned by its perceived inaccuracy and frustrated when their opinions were either ignored or invalidated.

Is it an uncomfortable fact for those Australian commentators who take a black and white view of the CCP that most Chinese are pragmatic and, overall, supportive of their government. An Ipsos poll in June found that 87 per cent of Chinese thought their country was “headed in the right direction”, by far the highest proportion found in any of the 26 countries surveyed.

What all this means for Australia is that if we insist that only those Chinese student voices critical of the Chinese government are authentic and deserve our support, a majority of Chinese students will be alienated, unfairly. And as Frances Adamson pointed out, this would be an affront to Australian values, where all in society have a right to speak up.

Professor James Laurenceson is deputy director of the Australia-China Relations Institute (ACRI) at UTS. He has previously held academic appointments at the University of Queensland, Shandong University and Shimonoseki City University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.