Australian Resilience to Election Interference

Reports of foreign election interference in the US, UK, and EU have brought our own vulnerability under closer examination. But do we have a sound understanding of what it all means? We may be only at the beginning of negotiating the issue as our discussion of “civic education” and “media literacy” matures into a wider notion of national resilience.

Foreign election interference is a hot topic. Voters in numerous democracies are allegedly being targeted for manipulation by hostile foreign actors. In response to this, Australia’s Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters has recommended an electoral “cyber task force” be created. The committee initially examined matters of technical security before broadening its scope to include “disinformation.” In a March 2019 report, it recognised disinformation campaigns as a credible threat to democracy, affirming with other international signatories the need to protect citizens and electoral processes from foreign interference. The report calls for greater corporate accountability from media publishers, improved critical thinking and a taskforce focus on “systemic privacy breaches” to safeguard voter information.

Intrusion is just the beginning

Our political parties and businesses collect quite a bit of sensitive voter and consumer information, and the committee has rightly observed that this information should be better safeguarded from theft or damage. But information operations (IOs) are about more than cyber-attack. In the case involving the compromise of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 US Presidential campaign emails, technical intrusion was just one facet of a lengthy IO campaign to manipulate voter perception and behaviour. Similarly, hostile influence operations may also incorporate legitimate business activities, underpinned by insights gained from stolen data. Considering these possibilities, we should be thinking about how to deal with the possible after-effects of breaches. Were Australians to be targeted with propaganda and business pressures built upon stolen information, how would we recognise it? And how would we, or our institutions, cope?

Disinformation follows

Our understanding of the technical aspects of electoral interference should be complemented by an understanding of our non-technical vulnerabilities such as how our own culture and conventions facilitate the spread of disinformation. As a 2017 US Congress Report on the 2016 US election noted, disinformation is most effective when it amplifies existing issues and biases. Using paid social media advertising and online forums, a wide range of existing US interest groups were successfully agitated by Russians employing online disinformation techniques to appeal to US interests, sometimes going so far as to engineer physical confrontations of US protesters and counter-protesters. As one Russian formerly employed in disinformation work told journalists, “We raised social issues and other problems that already existed in the United States, and tried to shine as bright a light as possible on them.” The strategy here is to unnaturally amplify an authentic element of democratic debate, while concealing its authors and aims – like a cuckoo concealing its eggs among the others in the nest.

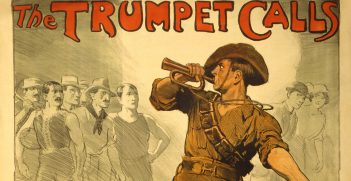

As deception techniques continue to evolve in the digital era, researchers of information warfare sometimes disagree on how to define IO activities. This is, in part, because conventional understanding has borrowed heavily from the history of military operations and digital media has taken IO well beyond the battlefield while burgeoning with the growth of behavioural sciences. Back in 1937 for instance, the US Institute for Propaganda Analysis tried to educate the US public with a short list of just seven propaganda techniques. There are now approximately 50 identifiable propaganda methods, many of them commonly employed in the persuasions of marketing and politics. However, of particular interest here is the way in which disinformation engages disenfranchised or vulnerable audiences, while deliberately concealing its source.

Developing disinformation resilience

The United States, United Kingdom, and wider Europe offer useful observations on the experience of disinformation and electoral interference. The most comprehensive come from the Baltics, where an understanding of national resilience has grown to accommodate a Disinformation Resilience Index (DRI). Each country DRI offers a report card on media independence, vulnerable groups and analysis of identified propaganda themes, with recommended improvements. It would be a positive contribution to Australia’s democratic debates to regularly publish updates of its own DRI. We ought to consider the needs of our most vulnerable groups, rather than surrender their anxieties to disinformation. We ought to understand the gap between what we have now, and what we may require additional legal reforms and funding to support. And we should have faith that allowing the wider Australian community to own and drive this discussion will only help to grow our resilience to information designed to agitate and disenfranchise us.

Recommendations

Three-quarters of Australians say they have experienced fake news and are worried about it. They believe that media outlets and the government should more actively prevent its spread. Social media companies have responded by closing accounts displaying “inauthentic behaviour,” and the Australian government continues to provide rigorous guidelines for political advertising. But information warfare’s deliberately deceptive techniques present unique challenges for traditional regulators. Andrés Sepúlveda, a hacker in prison on charges relating to the 2014 Columbian election, has extensive experience of this, claiming to have helped manipulate elections across Latin America. He believes that operations attempting to rig elections occur on every continent. Hackers have been completely incorporated into modern political operations.

Online business meanwhile, provides hostile foreign groups with commercial data and tools that legally target international audiences. Information warfare has never been cheaper, or more lucrative, as seen in a recent report on a network of Balkan Facebook pages targeting Australians. Media publishers should be more alert to this, but they cannot shoulder all of the responsibility. We should be looking inward to understand what makes disinformation’s messages most attractive to us. It’s time for an earnest discussion about our society’s fault lines, civic education, digital media literacy and the limited resources and funding that educators and not-for-profits have to support the growth of our information resilience. It’s time for earnest consultation with media and education sectors on what people want and need to know about their media, civic participation and security. How well we do this will determine to what extent information is a source of our prosperity or a weapon that harms us.

Ivana Troselj has worked for the Museum of Australian Democracy and the Australian Defence Organisation. She is currently a PhD candidate with UNSW Canberra and gratefully acknowledges the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. The views in this article are her own.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.