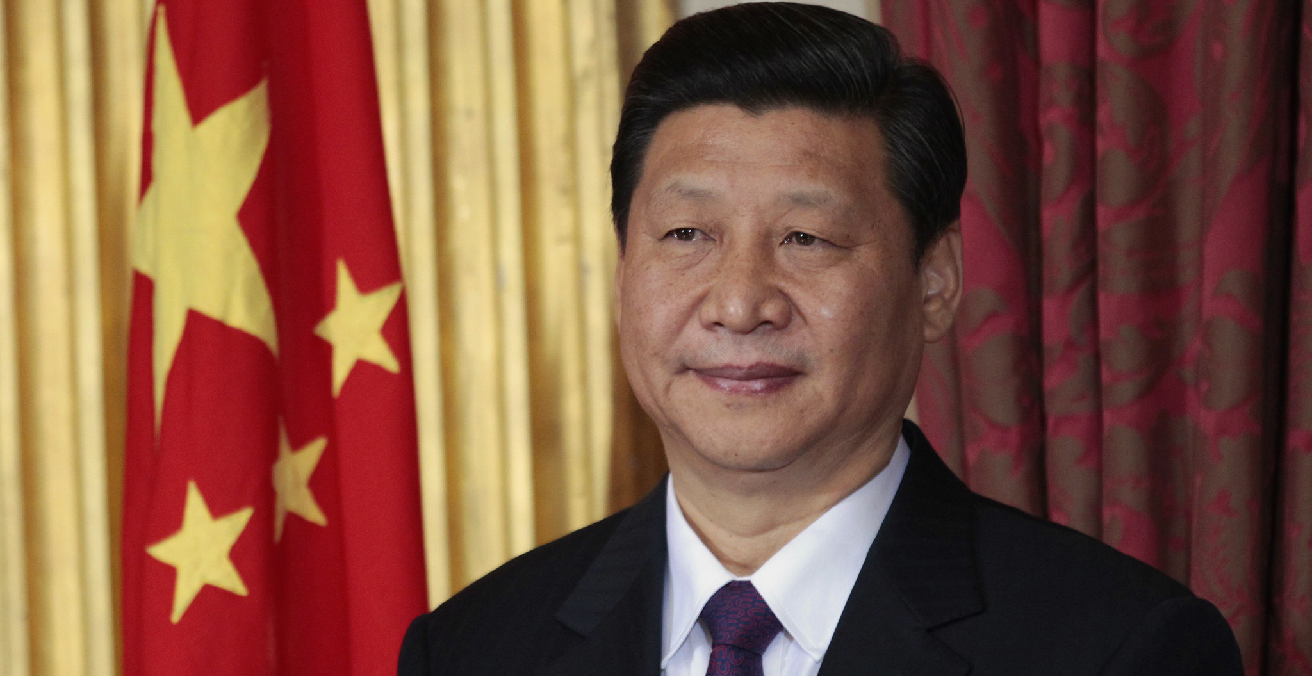

As China Squeezes the Australian Economy, Canberra Should Borrow a Page from China's Book

Tensions have been brewing between the East and West, expedited through mismanaged situations regarding political issues and sensitivities over the COVID-19 pandemic. Amidst global tensions, it is no secret that Australia and China have not been seeing eye to eye.

Before recent developments, Australia was seen around the world as an example of how Western democracies might engage with the rising Asian power of China. Together, the two nations had forged what looked like a détente – creating a bilateral trade relationship worth around A$240 billion per year.

But over the past few months, it has become clear that what Beijing wanted from Australia wasn’t a willing trading partner. What it wanted was complicity – a willingness to turn a blind eye toward Chinese ambitions in the region and the problematic ways they are starting to manifest themselves. And Australia hasn’t been compliant.

The source of the present breakdown in relations may have roots that go all the way back to 2017, when Australia announced its intention to ban foreign-sourced political donations. At the time, the government explained the move by pointing to reports of Chinese individuals attempting to influence its domestic affairs. Huang Xiangmo, a Chinese citizen and permanent resident of Australia, was accused of meddling in politics and barred from entry into Australia. His ties with the Chinese Communist Party were cause for grave concern, and Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull was advised to avoid events where Huang might be present as a matter of national security. Chau Chak Wing is another such individual who has been defamed for bribery and acting as an agent of China’s soft power.

This display of distrust did nothing to win any favours from China, and while the Chinese government has not responded to these events, it won’t be the last time that Australia made moves that appear to have upset Beijing. In 2018, Australia became the first nation after the US to enact a ban on the use of any Huawei equipment in its growing 5G cellular networks. It was the first in a series of manoeuvres meant to curb Chinese investment in critical sectors of the Australian economy. This sparked accusations of Chinese discrimination, triggering the Chinese ambassador, Cheng Jingye, to quickly point out that the allegations were unfounded and the ban was a political move to curb China’s growth by means of boycotting.

Around the same time, Australian policy experts began to question Chinese intentions concerning genetic testing, as they worked to expand their domestic genetic database for surveillance use. From the outside, it has been suggested that the Chinese government is building the system as a check against dissidents, but there are also some signs that it has a more global intent, despite BGI Group’s denial, paired with the support of Australian Health Minister Greg Hunt. It is believed that the health company was harvesting genetic material through their COVID-19 tests, but health experts have pointed out that there is a miniscule risk this data would be sufficient in any kind of misappropriation.

All along, the Chinese government seemed to limit its response to protestations registered through diplomatic and media channels. But that came to an end when Australia became one of the leading global voices calling for both an investigation into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic and an end to Chinese intervention in Hong Kong, Taiwan, the South China Sea, and elsewhere in the region.

As a result, Beijing began an escalating trade war with Australia. Last May, they slapped an 80.5 percent tariff on Australian barley, while simultaneously placing restrictions on beef imports. Then came a 200 percent tariff on Australian wine, along with additional curbs on coal, copper, and timber. The combined tariffs and restrictions are already having a devastating effect on the Australian economy, which had already entered recessionary territory.

These actions have also laid bare Beijing’s true intentions – which involve using its outsize economic leverage to extract political concessions from Canberra. More than that, though, it’s looking like China has decided to make an example out of Australia. They appear to be sending an unmistakable message to the rest of the world that outsiders can only interfere with their ambitions at their peril.

But in response to that message, Australia must send a clear response that it is not going to relent and submit to Chinese hegemony. And it looks like they’re doing that, with reports of outreach to India seeking to strengthen bilateral trade ties. And despite the short-term pain, it is of critical importance that Canberra succeeds in weaning itself off Chinese dependence. The Australian government has yet to act on their proposed plans on strengthening ties with India, while a dispute between China and India has recently erupted over a shared border. Whether this comes on the tails of Australia’s new resolve to work on free trade with India is unclear.

Australia is engaging its allies to push back against Beijing’s attempts at economic coercion. The present situation may be a preview of what is to come for other nations that have become economically dependent on China. That list, of course, is headlined by the United States, which itself has had no shortage of trouble with China in recent years. Where Trump was concerned, the administration mismanaged their relationship with China, but Biden’s strategy is to put together a team of experts on Asia focused on inclusion and will be reviewing all policies under Trump and the trade deal, putting Australia in a difficult position as an American ally.

At present, it is clear Australia cannot replace its economic losses fast enough to avert the worst outcomes. And that means it can’t yet afford to offer a full-throated condemnation of China’s actions. But what it can do is to play the same game the Chinese have been playing all along.

That game involves making public efforts at rapprochement while working feverishly behind the scenes to serve its own interests. By doing so, it is possible that Australia can buy itself the time needed to rearrange its economy to free itself from what is increasingly looking like a well-laid trap. The only question that remains is how well Australia will execute that strategy. And only time can provide an answer to that question.

Anton Lucanus holds a BSc from the University of Western Australia and is the Founder of Neliti, Indonesia’s largest digital library with over 200,000 publications and 3 million monthly website visitors. Anton is a past recipient of the AIIA’s Euan Crone Scholarship.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence, and may be republished with attribution.