Arab Reaction to Trump Plan Reveals Rising Strength of Israel And Increasing Palestinian Isolation

While states such as Israel, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia have issued tepid statements of support for the US “peace plan,” other states are not so convinced. What will this mean for stability in the region?

The Arab League has joined the Organisation of Islamic Countries (OIC) in formally rejecting the Trump plan to end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The OIC had earlier called on its 57 member-states “not to engage with this plan or to cooperate with the US administration in implementing it in any form.” Despite the appearance of Arab and Islamic solidarity, the response of individual governments has been far more nuanced, revealing an increasing frustration with the Palestinian issue and a desire to break the longstanding Arab League position of rejecting normalisation of relations with Israel or even recognising the existence of the Jewish State. Egypt, with whom Israel has enjoyed a state of peace since 1979, and Saudi Arabia issued tepid statements of support for US attempts to broker an end to the conflict. Oman, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates all sent their ambassadors to attend the unveiling of the Trump plan.

After Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu held talks with Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of Sudan’s sovereign council on 3 February, the Israeli leader announced that the two countries have agreed to begin normalising relations, a move the Palestinians quickly condemned as a “stab in the back.” The announcement constitutes a landmark diplomatic achievement for Israel and one replete with symbolism. It was in Sudan that the Arab League adopted the famous “Three No’s of Khartoum” position, whereby the Arab world resolved that there was to be no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, and no negotiations with it. The meeting between the Israeli Prime Minister and the transitional government of Sudan took place in Entebbe, Uganda, the city where in 1976 Israeli commandos launched a spectacular raid to liberate hostages after an Air France flight had been hijacked by Palestinian militants and given shelter in Uganda by Idi Amin. The raid was led by Yonatan Netanyahu, the elder brother of the Israeli premier, who was killed during the operation.

The reaction of the Arab world reflects a marked thaw in attitudes towards Israel, brought about by an increasing realisation that Israel poses no threat to those who do not threaten it, a mutual interest in confronting Iran, and a desire to achieve economic cooperation with a country that has shown itself uniquely adept at building prosperity despite a lack of natural resources. Equally, it reflects a willingness to view Israel as more than merely a party to an enduring and possibly irreconcilable conflict. This is a major blow to the Palestinian strategy of maximising its bargaining position by making Israel’s engagement with the Arab world conditional on it first meeting Palestinian demands.

However, the gradual erosion of uniform hostility to Israel in the Arab world may create the conditions necessary for eventual peace, or at least lead to the resumption of bilateral negotiations. Despite reflexively calling the proposal a “hoax” and a “fraud” and succeeding in obtaining official Arab League support for its position, the Palestinian leadership will be concerned by the growing number of Arab League member-states who no longer see Israel as an enemy to be relentlessly fought. This may in turn lead the Palestinian leadership to make some constructive gesture towards peace to shake of the accusation of intransigence.

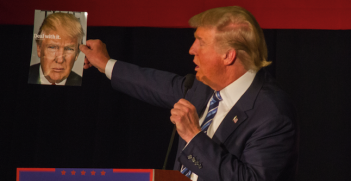

Ultimately, peace can only be achieved through compromise. Compromise requires accepting less than one’s optimum outcome. The Palestinians may feel that having to negotiate over the terms of their statehood, a right they hold to be self-evident, is compromise enough. Indeed, at the Arab League meeting in Cairo, Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas held aloft a series of maps titled “The Palestinians Historic Compromise” purportedly showing a progression from a wholly Arab Palestine in 1947 to the far smaller lands offered to them in the Trump plan. The maps, highly misleading given that an Arab State of Palestine has never existed and that Palestinian autonomy has increased over time in spite of successive rejections of internationally-brokered two state solutions, do reveal a key reality of Middle-East peacemaking. Time is not on the side of the Palestinians, and each missed opportunity has left their national movement in a weaker position, while Israel, now in its 72nd year of statehood has benefited from the decisions of its early leaders to compromise, accept less, in pursuit of the ultimate goal of statehood and the upbuilding of a national home.

In 1937, a British Royal Commission, which for the first time offered partition of the land and a two-state solution, concluded that “half a loaf is better than no bread”, and while “partition means that neither will get what it wants … both parties will come to realise that the drawbacks of partition are outweighed by its advantages.” The “advantage” offered to the Jews at that time, was a miniscule Jewish State, a society which they could organise according to their own ideals, a place to grant refuge to those needing it, and enlarge Jewish cultural and scientific achievements. This opportunity was too meaningful to reject, even if at that time the Jewish State offered was on a mere 4 percent of the originally mandated territory.

The question of partition was rejected out of hand by the Arab side, which instead pledged the “liberation of the country and establishment of an Arab government.” The ensuing wars in pursuit of “liberation” have resulted in displacement, loss of life, and a corresponding loss of political leverage on the Palestinian side. The Palestinians, in rejecting this later proposal without so much as comment or counter-offer, are now finding that it is they that are becoming increasingly isolated, and are losing the sympathies and attention of even their most dependable supporters.

Alex Ryvchin is the co-Chief Executive Officer of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry. His new book is “Zionism – The Concise History”.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.