APEC's First 25 Years and the Road Ahead

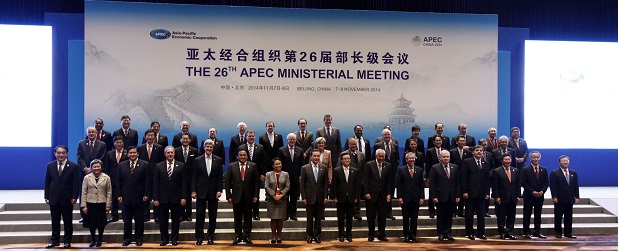

APEC leaders meet today in Beijing , 25 years after the APEC process was launched in Canberra in 1989. According to Andre Elek, some early hopes have been met, while others have been dashed.

APEC continues to provide economies in the Asia Pacific region with an opportunityto share information and expertise, identify opportunities for cooperation, anticipate problems and encourage each other to adopt policies for economic integration andsustainable growth. This work, similar to that of the OECD, is contributing to more efficient responses to shared challenges including urbanisation, food safety, disaster management and the promotion of e-commerce. APEC has also paved the way for China to engage in international economic cooperation soon after its opening to the outside world, then to facilitate its entry to the WTO.

The APEC group of economies is the most dynamic and integrated in the world. Average tariffs have been lowered to just over 5 per cent and cooperative arrangements save billions of dollars every year. Most components and products flowing along 21st century supply chains do not face significant border barriers. This opening has largely been due to unilateral decisions of APEC governments, as they learn from the success of others and capitalise on new opportunities created by radical improvements in transport and information and communications technology. Even without an APEC-wide trading bloc, the ratio of actual to potential trade among APEC economies is higher than for the EU.

Border barriers to trade remain on a few sensitive products, largely agriculturalcommodities and low-tech manufactures. These problems, left over from the 20th century, are proving politically intractable in the bilateral and regional tradenegotiations and in the WTO. Developed APEC economies did not meet their commitment to achieve free and open trade by 2010 and no APEC economy is likely to meet the next 2020 Bogor deadline. Fortunately, these products account for a rapidly shrinking share of international commerce, so this protection is not a serious problem for the integration of the Asia Pacific.

For many years, the business sector has been telling governments to shift attention from tedious negotiations aiming to achieve tiny gains in liberalisation of sensitive products, to a focus on reducing more significant costs of international commerce.The business community’s priorities are to improve trade logistics and to reduce theconfusion caused by needless differences in economic regulations, including the proliferation of rules of origin. Recent research by the World Bank and the WorldEconomic Forum concludes that supply chain barriers to international trade are far more significant impediments to economic integration than tariffs. It is time to build on APEC’s trade and investment facilitation work to seize such practicalopportunities.

APEC leaders are committed to transforming the Asia Pacific into a comprehensivelyconnected region by 2030. China has led the design of an APEC Blueprint for Connectivity, setting out opportunities to improve physical, institutional and people-to-people connectivity by 2025. To implement this blueprint, a detailed plan will need to be backed up by objectives like the emerging APEC Single Window system, part of improving crucial transport, communications and energy networks. Building up the skills and institutional capacity required to attract adequate investmentrequires APEC to invest seriously in capacity building.

Delivering significant improvements in physical, institutional and people-to-people connectivity will also need sustained political commitment to and cooperation on some significant flagship initiatives for connectivity. One such opportunity isupgrading the efficiency of major ports and airports. Another is to take advantage of Myanmar’s decision to engage with the international economy to build high-capacity transport and communications links between East Asia and South Asia. The new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank could commission full-scale feasibility studies of such opportunities.

Unfortunately, APEC is unlikely to make the necessary commitment to better connectivity in the near future. Its concept of ‘regional economic integration’ is the dream of a Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific (FTAAP). This is a disappointing diversion of scarce policy-making resources. Negotiations for an FTAAP cannot be expected until the outcome of the drawn-out Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiationsbecomes clearer. Trade negotiations alone will not deliver the Bogor goal of free and open trade and economic integration.

25 years ago, APEC was the only forum that brought East Asian economies together with their trading partners across the Pacific. Now, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the G20 offer other opportunities for cooperation. To work alongside RCEP, APEC needs to widen its membership to include all of ASEAN and, in due course, India. New members can demonstrate their capacity tocontribute as well as benefit from APEC membership by working to improveconnectivity with neighbouring countries.

Perhaps the biggest disappointment of its first 25 years is APEC’s inability to support the WTO. There has been little collaboration on an achievable agenda fornegotiations on 20th century issues or on devising rules for new issues raised by radical changes in the nature of international commerce. Rather than turning their backs on open regionalism and trying to negotiate an Asia Pacific trading bloc, APEC leaders should lead a G20 discussion on rescuing the WTO. This would return to APEC’s original commitment to preserve and strengthen an open, non-discriminatoryinternational trading system, to which Asia Pacific economies owe their success.

Andrew Elek is Research Associate at the Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University. He was the inaugural Chair of APEC Senior Officials in 1989. This piece was originally published by East Asia Forum. It is republished with permission.