APEC Leaders’ Meeting Exposes Policy Fault Line

With differing views on trade, multilateralism and the future of APEC itself, the latest APEC leaders’ meeting presented much more to think about than the colour of the delegates’ traditional costumes.

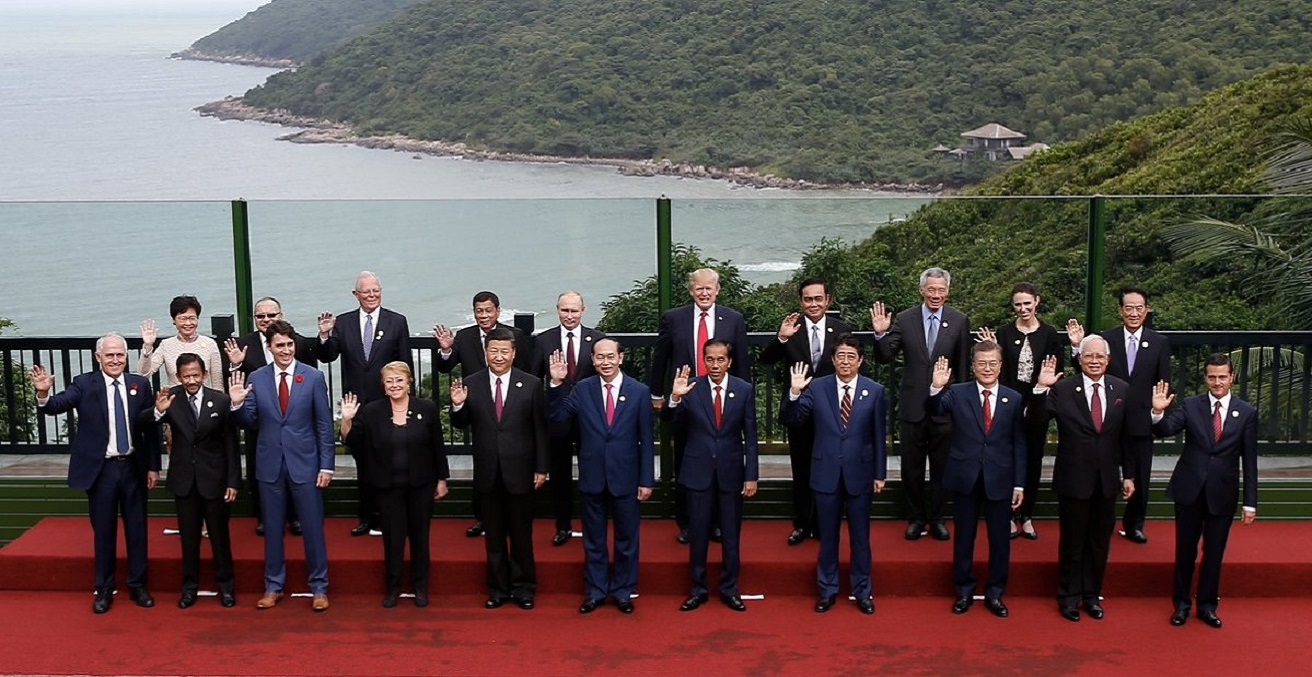

Vietnam welcomed some of the world’s leaders last week as it hosted the 2017 APEC Leaders’ Meeting. With Presidents Trump, Putin and Xi in attendance, the meeting exposed a difference in perspectives on trade, multilateralism and the future of APEC itself.

The APEC Leaders’ Meeting hosted by Vietnam in Da Nang last week proved far more engaging than most seen over the past 25 years. Previous annual get-togethers have been low key set-piece shows, focusing largely on somewhat mundane international trade issues with most of the colour provided by the host-nation costumes that leaders traditionally don at the end of proceedings.

Perspectives on globalisation

What made the Vietnam APEC meeting distinctly different was the policy fault line that has emerged since the election of US President Donald Trump over the benefits or otherwise of globalisation. During the meeting we heard President Trump and President Xi of China promote alternative perspectives on globalisation which has always been central to APEC’s mission, which, after all, has the motto, “advancing free trade for Asia-Pacific prosperity”. A key policy difference, pivotal to how globalisation in the Asia-Pacific region progresses, is whether international trade agreements amongst APEC members are primarily struck on a bilateral or multilateral basis.

President Xi has become the standard bearer for the existing variant of multilateral globalisation that has turbo-charged the Chinese economy since the 1980s, making China the largest Asian economy and lifting hundreds of millions of its citizens out of poverty. However, President Xi did concede that globalisation now needs to be “more open, more balanced, more equitable and more beneficial to all.”

Reflecting his bilateral ‘America First’ approach, President Trump on the other hand stressed the need for “fair reciprocal trade” underpinned by stronger enforcement of international trade rules by the World Trade Organization and reduced bilateral trade imbalances between the US and its trading partners.

Trans-Pacific Partnership

On the sidelines of the APEC meeting, we saw the consequences of President Trump’s alternative perspective with the attempted relaunch of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which no longer has the US as its designer, navigator and pilot. The original TPP, which could have been a stepping stone towards establishing a more comprehensive free trade area for the Asia-Pacific, was almost shredded earlier this year when the US withdrew.

Australia and Japan took the lead in negotiating a revamped TPP (more formally the Comprehensive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership). Known as TPP11, it includes Japan, Australia, Brunei, Chile, Vietnam, Canada, Mexico, Malaysia, New Zealand, Peru and Singapore, with China still excluded. Although substantial progress had been made on TPP11 in the lead up to the Da Nang meeting, it remains to be finalised due to Canada’s last minute reticence.

Leading the world

Meanwhile, the APEC region continues to outperform the rest of the world economically, growing 3.4 per cent in 2016, half a per cent higher than the rest of the world’s 2.9 per cent growth. Regional growth is also on an upward trajectory. For the first half of 2017 it neared 4 per cent, more than half a per cent higher than last year’s.

International trade has been instrumental to Asia-Pacific growth with a remarkable turnaround in merchandise exports. Exports actually contracted 6.6 per cent last year, but have rebounded in the first half of 2017 to grow by 10.4 per cent. Merchandise imports are also up by near 12 per cent. This means the trend—since the 2008-09 global financial crisis—of Asia-Pacific trade growth falling below regional GDP growth, appears at last to have broken.

Additionally, APEC attracted 53 per cent of global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows last year. Although valued at less than USD$1 trillion (AUD$1.3 trillion), FDI remains relatively small compared to the value of total trade flows in the region. This suggests a higher policy priority be given to enhancing foreign investment given the poverty alleviating, income boosting benefits it can bestow, benefits which are potentially as high, or higher, than those stemming from increased international trade.

The future of APEC

What is the future for APEC then at this juncture? A touchstone of APEC, the 1994 APEC Bogor Declaration, called for free and open trade and investment in the region by 2020. This still remains central to APEC’s mission, although with the difficulties the TPP has experienced, (not a fully APEC-wide instrument for attaining open trade and investment in the region by 2020) the Bogor goal will not be met in a literal sense. This has opened up discussion within APEC about its future role and aspirations beyond 2020.

Although enhancing international trade has remained central to APEC’s mission over the years, there has been growing recognition that trade is but one means, amongst many, to the more significant end-goal of higher economic development and living standards across the region.

APEC has also recognised that higher economic growth needs to be more inclusive and that ways to improve growth and ensure greater inclusiveness include structural reform, better access to quality education and skills development, improved infrastructure and better coordinated labour market policies. Governments should therefore continue to broaden APEC’s remit beyond international trade to macroeconomic issues along these lines and to reshape public perception of its wider pro-inclusive development agenda.

The United States now regularly refers to our region as the Indo-Pacific rather than the Asia-Pacific. It is therefore not inconceivable, should India and other South Asian economies join the present grouping, that APEC eventually becomes ‘IPEC’. Given the growing importance of India as an economic partner, Australia should welcome such a development.

Tony Makin is professor of economics and director of the Griffith APEC Study Centre at Griffith University, and has previously served as an international consultant economist with the IMF Institute based in Singapore. He has worked as an economist in the Australian federal departments of finance, foreign affairs and trade, treasury, and prime minister and cabinet.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.