Anwar Injustice in Context

Malaysia is due to reach high-income nation status by 2020. Unfortunately it will continue to have third-world politics for some time to come.

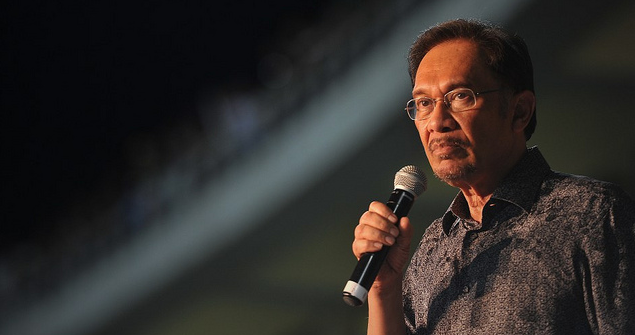

Most foreign observers will have heard of Anwar Ibrahim and the persecution brought against him by the Malaysian Government. The country’s highest legal authority has dismissed his appeal and upheld his five-year sentence for sodomy. The trial was originally scheduled for two days but lasted for eight. I had the privilege to attend one. The arguments were thorough; the judges listened and questioned submissions made. They took their time, around three months, to make their decision. A first-year law student would be able to tell that the evidence did not support a conviction. The High Court of Malaysia recognised Anwar’s wrongful conviction, which was subsequently overturned by the Court of Appeal. Yet, finally, the Supreme Court has confirmed his “guilt’’. The judgement is surprising but, in the context of Malaysia’s political and legal state of development, understandable.

Malaysian politics: A fragile spider’s web

Anwar was the leader of the opposition coalition, Pakatan Rakyat (PR), or People’s Pact, which comprises three parties: Anwar’s Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR), which holds 29 seats; the Democratic Action Party (DAP), 37 seats and the Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS), 21 seats. It is hardly a cohesive coalition. DAP is a secular, socialist party while PAS is an Islamic party. In one state where PAS has been able to form government (Kelantan), the party has stated its aim of introducing hudud law, a version of Islamic law. This hardly sits well with DAP and the PR coalition at the national level.

The ruling coalition, Barisan Nasional (BN) has governed Malaysia since independence in 1957. The dominant party within the coalition is the United Malays National Organisation (UNMO) with its minor parties the Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu (PBB), or United Traditional Bumiputera Party, the Malaysia Chinese Association (MCA) and the Malaysia Indian Congress (MIC). The last two are bit players in the coalition. They hold seven and four members in the House of Representatives, respectively, but their presence allows BN to claim it represents all racial groups in Malaysia.

During the 2013 federal election BN won a significant majority of seats in the federal parliament despite only gaining a minority of the popular vote. It was the most significant threat to BN rule in its history.

Legal tools of the trade

There are plenty of choices for government figures to crack down on dissent. Anwar was charged under the “unnatural offences’’ provision of the country’s anarchic penal code (section 377B), which categorically outlaws sodomy. It has been invoked only a few times. This however is not the usual weapon of choice for the government in cracking down on opposing opinion. The Sedition Act, a colonial era piece of legislation, makes it unlawful to “bring into hatred or contempt or to excite disaffection against any Ruler or against any Government’’. There are other provisions that further its reach but the general aim is to crack down on dissent. Whilst such a provision may have been helpful during the Emergency period, it is hardly a piece of legislation that deserves the light of day in the 21st Century. The current prime minister went so far as to promise its repeal. Since that promise, many have been arrested or questioned by the police under its provisions. Opposition politicians, academics and ordinary members of the public have suffered under this act. The government has even pledged to step up its use, while other groups (in a similar tradition to 25 prominent Malaysians who called for moderation in the political discourse) have demanded that the government stop using the Act. This will not happen because UNMO is highly dependent on the Act and has founded its legitimacy on the “survival of the Malay race’’.

Poisonous politics in an apartheid state

Last year, Prime Minister Rajib Razak backtracked on his pledge to repeal the Sedition Act. The central reason, put forward in various ways, is that the repeal of the Act would threaten the Malay race, ignite race riots akin to those that occurred in the 1960s and risk tearing Malaysia apart at the ethnic seams. Or as a former chief justice put it, Malays must unite to avoid becoming “Red Indians’’ in their own country. This is despite the fact that the country has a majority Malay population, that all current and former prime ministers are Malay and that all positions of power are held “disproportionately by Malays’’.

The “special rights’’ enjoyed by Malays are enshrined in the constitution (s153) and strengthened by various parliamentary Acts. This has institutionalised the differential treatment Malaysians receive along ethnic lines and has served as a rallying cry for extremist Malays. As a Malaysian-Chinese businessman told me: “If you are Chinese, the Government will not give you any work’’.

In this context anything construed as criticising Malays is seen as seditious. UMNO hosted an International Forum in late 2014 with the subject “A Hyperconnected World: Challenges in National Building’’. The forum admitted that during the 2013 elections, in the online realm, the party was thoroughly beaten by clever opposition tactics. The panellists included representatives from China, North Korea, Cambodia and the Minister for Home Affairs of Malaysia. The authoritarian undertones of how online discussion should be regulated were obvious.

Uncertain future

Last year the Government announced that the Electoral Commission would be undertaking a review of the number of federal seat boundaries. It is hardly expected to be fair. The previous electoral commissioner has joined Perkasa, an extreme right-wing Malay organisation partially responsible for the Government’s unwillingness to repeal the Sedition Act. If, during the next general election, BN maintains its parliamentary dominance but loses the popular vote by a significant margin, what will be the consequences?

Anwar sentence in context

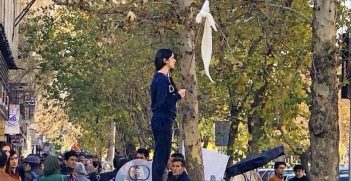

Anwar is not the political dynamo he once was. Gatherings outside the Supreme Court during the hearing last year were quite underwhelming. Yet the strategic use of the police and judiciary to repress opposing voices is questionable as a strategy for re-election. The dynamics of the opposition coalition, PR, hardly make for a functioning opposition. Divide and conquer is much easier if they do not have something to unite and rally behind. Anwar’s sentence may serve a greater purpose after all.

Patrick Hill is a former intern at the Australian High Commission, Kuala Lumpur and AIIA National Office. He has a degree in Law and International Relations from Griffith University and is currently pursuing a Masters in International Security Studies. He can be reached at patrick.hill@griffithuni.edu.au. This article can be republished with attribution under a Creative Commons Licence.