African Union Seeks Rejuvenation

In a new year, the African Union has seen an opportunity to renew the organisation which seeks to unite the burgeoning continent. With 55 diverse and disparate members, the process is however fraught with challenge.

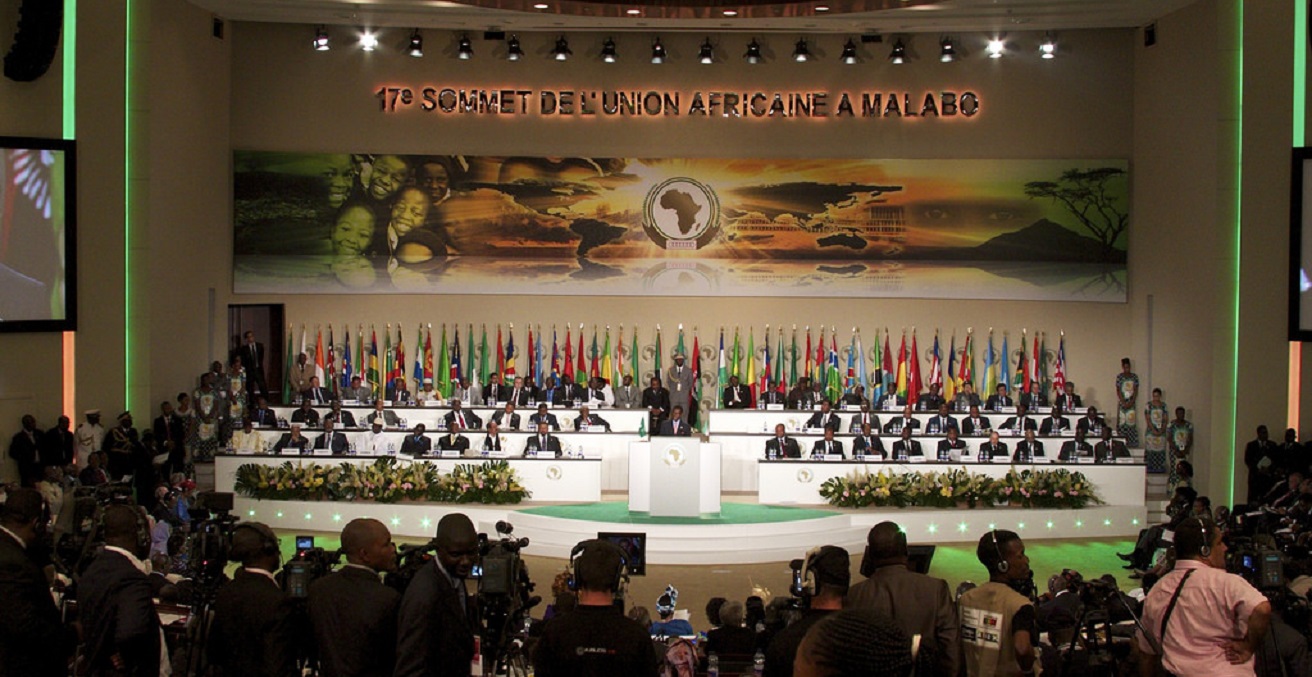

At 15 years old, the African Union (AU) is undergoing a major reform process after struggling, by its own admission, to live up to its progressive ideals and objectives. The reforms, led by Rwandan President Paul Kagame, aim to reorganise and streamline the pan-African institution to better deliver on its core mandate and add value to the governance of a continent home to 55 countries and 1.2 billion people. A new funding model seeks to reduce the AU’s financial dependency on external donors and take greater ownership of its agenda. Against this backdrop, a recent week-long high-level dialogue convened in Pretoria under the AU’s African Governance Architecture critically debated core governance concepts and challenges facing the continent.

The reforms come at a critical time for an AU facing persistent questions about its relevance, legitimacy and capacity to manage a highly diverse and dynamic continent. For example, in the face of acute violence in South Sudan, Somalia, Central African Republic, Libya, the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Sahel, the AU has tasked itself with ‘Silencing the Guns by 2020’. The Union is also trying to balance the competing imperatives of;

- Protecting substantial refugee and internally displaced populations,

- Facilitating easier continental economic migration via the African passport

- Preventing both deadly trans-regional crossings and the re-emergence of overt slavery, and

- Placating concerns in Africa, Europe and beyond about the implications of incoming migration for national security and unemployment.

More broadly, the AU seeks to implement its ambitious, long-term continental integration and development plan, Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want, along with supporting the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. These responsibilities demand more committed and accountable pan-African political leadership, more adequate mobilisation of resources and more effective institutional structures.

The Kagame reform package, The Imperative to Strengthen our Union, was formally endorsed by the AU Assembly at its January 2017 summit. Four main outcome areas are identified. First, streamlining the AU’s focus to the four ‘priority areas’ of political affairs, peace and security, economic integration, and Africa’s representation and voice on the global agenda. Second, realigning the AU Commission’s organs and agencies to more effectively and efficiently support these priority areas while making them more representative by implementing staff quotas for women and youth. Third, improving AU management by limiting summit agendas and controlling engagement by external parties by replacing one of the two annual ordinary summits with a subsidiarity coordination summit, enhancing the AU’s ability to sanction its member states for non-compliance with AU decisions, and revising leadership roles and staff recruitment practices.

The final, critical area is AU financial reform, which is being spearheaded by Donald Kaberuka, a fellow Rwandan and former president of the African Development Bank Group. External donors currently fund over 70 per cent of the AU’s USD$782 million (AUD$998 million) operational and program budget, undermining the body’s autonomy and credibility. Part of the problem is that only about half of AU member states pay their annual membership fees—competing previous proposals to raise indigenous revenue for the AU have failed. In its July 2016 Summit in Rwanda, the AU adopted the Kigali Financing Decision with the target of self-financing 100 per cent of the AU’s operational budget, 75 per cent of its program budget and 25 per cent of its peace operations budget. To achieve this, the AU agreed to impose a phased-in 0.2 per cent levy on all eligible imported goods into Africa, raising USD$1.2 billion in annual revenue by 2020. This is coupled with a new system for assessing financial contributions based on capacity, solidarity and equity, and new oversight and sanctioning measures.

The Kagame and Kaberuka reforms, already underway and supported by a Reform Implementation Unit, target the January 2019 AU Summit for full implementation. Yet, the process has already attracted and been required to address criticisms from different quarters. For a start, some external interests oppose a stronger AU that could more effectively defend continental positions on matters such as trade, migration, counter-terrorism and global inequality. It has also been suggested the import levy could contravene the WTO’s trade rules. Others, meanwhile, are suspicious of the credentials and motivations of Kagame: he has brought stability and development to the country since the 1994 genocide but he is also accused of running a repressive regime and recently won a third term in office in Rwanda with 99 per cent of the vote following a constitutional amendment. Kagame will take over as rotating AU Chairperson in January 2018, from where he will pursue his continental reform agenda. His reforms, if implemented in full, would potentially shake up entrenched interests benefitting from current AU dynamics. Others conversely suggest the reforms are poorly conceived and too vague, lack proper consultation and are unlikely to have any real impact.

Behind these headline institutional and financial reforms there is an ongoing ideational and political contest over the type of ‘Africa We Want’, in particular over the so-called African Shared Values on governance upon which the AU draws legitimacy. From 4-8 December 2017, the AU Commission convened back-to-back high-level dialogues in Pretoria to advance these debates through engagement with expert (primarily African) speakers from the AU and regional organisations, political parties, academia, youth and other civil society organisations on the continent. As a Visiting Researcher with the AU Commission, I had the privilege to attend these dialogues, which were organised under the framework of the African Governance Architecture (AGA).

These high-quality dialogues and debates on democracy, development, governance, youth and equality in Africa demonstrated that the continent’s pan-African intellectual class was unafraid to pose the right questions and identify a range of potential solutions to the continent’s challenges, even if no consensus emerged. It was also evident that a new generation of effective, accountable and pan-Africanist leadership would be required to drive and implement governance and institutional reforms at the national and continental levels. These leadership qualities were clearly on display—from both females and males, the young and not-so-old—at the AGA high-level dialogues.

Dr David Mickler is a Senior Lecturer in Foreign Policy & International Relations at the University of Western Australia, Perth, and Coordinator of the UWA Africa Research Cluster. In November-December 2017, he was in Ethiopia and South Africa as a Visiting Researcher at the African Union Commission.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.