The ABC's China Interference Investigations

A Recent ABC documentary exposed elements of China’s political interference in Australia. However, while the program did much to inform the public and policymakers of these issues, it did not question Australia’s legislative response or engage with the core challenge that China’s overseas political activities pose for liberal democracies.

This article was originally published on Australian Outlook on 16 April 2019.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s (ABC) flagship investigative program Four Corners released a new documentary on the People’s Republic of China (PRC) political interference in Australia on 8 April. Titled simply, Interference, it’s a sequel to 2017’s Power and Influence, which helped pave the way for a series of controversial national security laws aimed at, among other things, cracking down on foreign interference.

There are a couple of interesting points of comparison between this new exposé and its 2017 predecessor, both presented by Nick McKenzie, one of Australia’s leading investigative journalists, working with a team of ABC and Fairfax colleagues.

First, the framing and presentation of the 2019 program are much preferable to its predecessor, from both a policy and public education perspective. The 2017 piece opened with a dramatic re-enactment of an Australian Security Intelligence Organisation counterespionage raid and layered on tension-laced sound and lighting effects, placing a series of distinct issues – political donations, control of diaspora media and student organisations – within an overarching espionage frame.

In contrast, the new documentary opens with a compelling, concrete case study in how the PRC party-state seeks to undermine critical voices in Australia’s Chinese-language media. This directs the audience’s focus towards the impact of PRC interference on political life in the Chinese communities of Australia, where its effects are overwhelmingly concentrated.

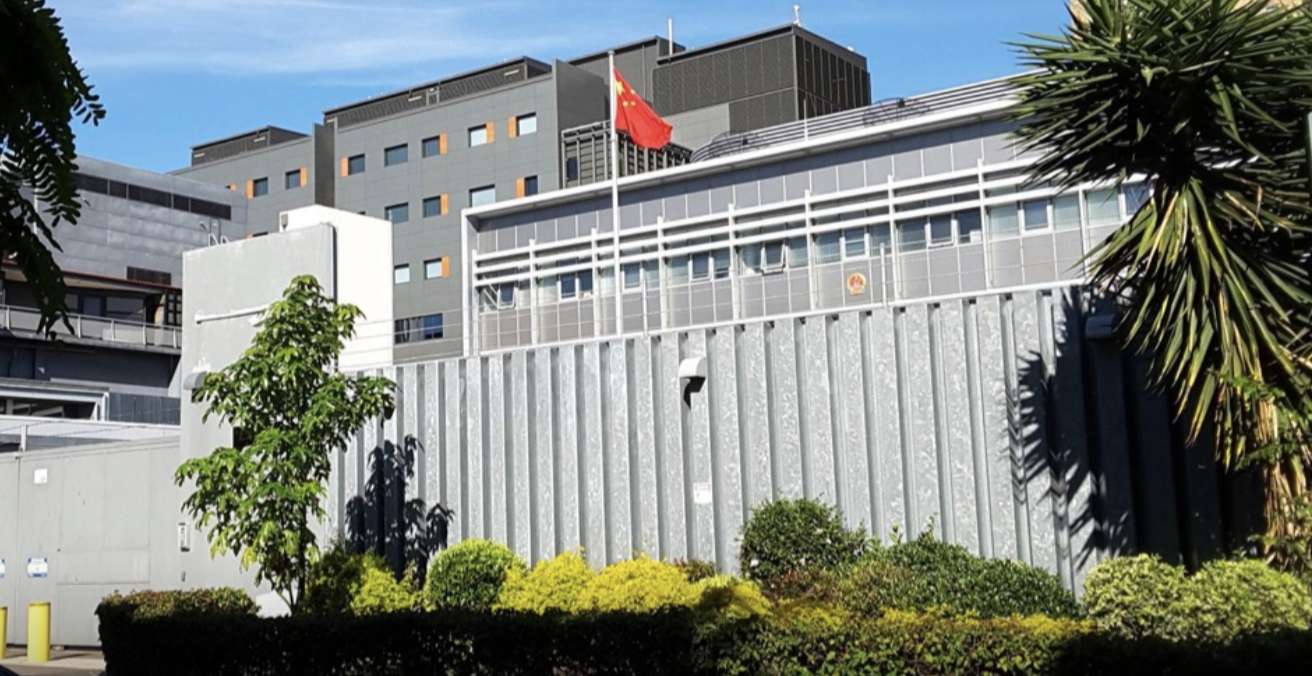

Using documents obtained under Freedom of Information, the program details precisely how the PRC consulate lobbied a local council to drop the Vision China Times (VCT), a Chinese-language outlet that is often critical of the Chinese government, as sponsor of its Lunar New Year event.

Thankfully, the PRC’s attempt ultimately failed, and the council maintained VCT as a sponsor in 2019. The case was well chosen for policy impact: it’s crucial that Australia’s local governments, rarely well versed in foreign affairs, understand that they are not somehow obliged to accede to demands from PRC consulates.

Credit, too, to VCT’s Maree Ma who spoke out, educated the local council and helped nail down the evidence.

Equally compelling is the evidence of censorship in Mandarin-language radio in Australia. However, it’s worth noting that the implementer of censorship in the latter case was not the Chinese consulate, but the Australian media mogul Tommy Jiang, who apparently enforces a pro-Chinese Communist Party (CCP) line on his presenters for commercial reasons. In a recording in the documentary, Jiang said:

If this continues, I will have trouble with my business partners in Melbourne and other partners too. You will also be in trouble. It has gone too far. You can’t just let them verbally abuse China and the Chinese Communist Party on air. Furthermore, their language is too vicious, you can’t allow that to happen.

But are these actually two examples of the same problem, namely, PRC interference in Australian politics? In one case we see a PRC consulate trying to interfere in a local council process. In another, we have an Australian media mogul dictating his own media’s editorial line.

John Garnaut, who advised Malcolm Turnbull on these issues, explains the link between the two. His description of the CCP’s rigging of the overseas media ecosystem to raise up pro-party voices while dampening critical ones should help a lot of non-China specialists grasp that issue:

Essentially, Chinese language media platforms in Australia have been co-opted largely, by the Chinese Communist Party. They’ve been incentivized. In some cases, they’ve been bought, or entered into various license arrangements and agreements. And on the other end of the spectrum, publishers, or independent voices who are prepared to have different views, have been intimidated. Their financial revenues have been squeezed. Advertisers have been threatened. So really, we’re talking about a full ecosystem of incentives and disincentives which dry up the space for independent voices, and reward people who are prepared to toe the line for Beijing.

Policymakers and other audiences need to understand that this is occurring, for addressing this problem could strengthen democracy in Australia more generally. Like the Murdoch family’s ongoing domination of Australia’s English-language newspaper industry, the CCP’s shaping of the Chinese-language media environment is enabled by lax media ownership rules and a lack of alternative funding.

However, a more direct CCP interference challenge escaped mention in the new documentary – that is extraterritorial censorship on PRC-based news and social media platforms that are widely used in Australia. This problem is especially urgent given that Australian politicians are now using WeChat to communicate with Chinese-speaking voters.

The WeChat platform’s subjection to PRC laws and party diktat means that Australian politicians’ posts on there could be subject to direct censorship – this has already happened to a member of parliament in Canada. Worse still, politicians who use WeChat could have incentives to sanitise their posts and avoid topics Beijing finds sensitive, lest they lose access to the platform.

Towards the end of the program, Garnaut speaks about his friend (and my colleague) Yang Hengjun’s detention in China in January on vague security-related grounds. There is little doubt that the Australian Government’s work on Yang’s case has been inadequate, as Garnaut points out:

I’d like to, at the very least, see some really strong statements about what this is, and why the importance of Yang to the Australian community, the Australian society.

Liberal MP Andrew Hastie, the Chairman of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security, also makes an important point on Yang Hengjun:

Mr Yang is an Australian citizen. He enjoys the rights and responsibilities of Australian citizenship. And so his detention, in a sense, is a detention of us all.

However, in light of Hastie’s Steve Bannon-inspired embrace of the rhetoric of “whole-of-society” threats and civilisational struggle against China, the Four Corners program accords him an extraordinary level of prominence and authority: he appears nine times, including in the opening sequence. At a minimum, some critical scrutiny of the nature and origins of his views on China appears warranted.

Interference concludes by pointing out that the CCP’s “campaign to silence others” has continued despite the enactment of Australia’s new national security laws, for which the ABC’s 2017 Power and Influence exposé helped lay the groundwork.

It does not, however, ask the obvious follow-up: how effective has Australia’s rapid-fire legislative response to the CCP’s overseas political activities been? Were the new national security laws not fit for purpose, or has their effect not kicked in yet?

The most salient recent case in this area of policy has been the revoking of pro-PRC political donor Huang Xiangmo’s permanent residency – but this was an act of Ministerial discretion, not enforcement of the new legislation.

Despite several references to the new national security laws, the Four Corners program makes no mention of the enormous concerns they generated among Australia’s legal experts and civil society over potential encroachments on core democratic freedoms. The Law Council of Australia likened the finalised version of the Espionage and Foreign Interference law to a “leap into the unknown for freedom of speech in Australia.”

As a result, the program ends without engaging the core public policy challenge that China’s overseas political activities present to a liberal democracy: how to balance freedom and security in an age of increasingly powerful authoritarian states, rising great power rivalry and a globalised networked information environment.

Dr Andrew Chubb is a British Academy postdoctoral fellow at Lancaster University, and an adjunct associate research scholar in the Columbia-Harvard China and the World Program. A graduate of the University of Western Australia, his current research examines the role of domestic public opinion in international politics in East Asia.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.