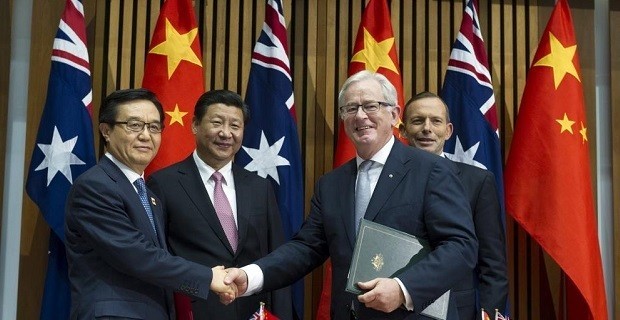

A New ChAFTA in China-Australia Relations

The China-Australia Free Trade Agreement is as much in China’s interests as Australia’s, argues director of the University of Sydney’s China Studies Centre Professor Kerry Brown.

The free trade agreement (FTA) which has been announced between China and Australia after almost a decade of discussion has been largely celebrated due to the favourable conditions it seems to grant to the agricultural sector. Tariffs on meat, fruit, and other foodstuffs will be reduced and in some cases removed in the next two to five years. Beef, lamb, seafood, horticultural products and some wines will all have export restrictions to China liberalised.

For Australian farmers, getting better competitive access to the potentially vast pool of domestic consumers in the People’s Republic is good news, and opens up a whole new alternative high growth market. But this is also an area where China is willing to grant access because it is clearly in its interests to do so. China’s food needs and its own food security are often uppermost in Chinese leaders’ minds. Having the best possible access to sources of supply from one of the largest agricultural players in Asia makes sense. In many ways, China has simply staked out a preferential partnership with Australia with the FTA to steal a march on other potential customers.

It is in the services sector however that the impact should be greatest. Australia needs to retool its trading relationship with its biggest partner so that it moves away from the addiction of resource provision and becomes far more based on services. This has been commented on many times in the last few years during the commodities boom which has made many in the country rich and helped it, almost uniquely, avoid the impact of the Great Financial Crisis felt in most of the other developed countries in the world. But the question has always been how this transition will actually be achieved. Four fifths of the Australia economy is in services. But of the AUS$110 billion of goods exported to China in 2013, only AUS$6 billion was in this sector. That figure needs to increase, quickly, especially at a time when demand for Australian resources in China is falling and China’s growth rate is coming down.

The FTA covers two broad areas in the services sector. The first is to open up access in China for providers of architectural, tourism, and healthcare sectors, so that it is easier to operate domestically. Tourism companies can open wholly Australian owned hotels and companies, and healthcare providers can operate private hospitals or care providers. The latter is again potentially a big deal. It is likely as Chinese become wealthier, more urbanised and live longer that their needs for treatment will increase, and more people will have the income to pick private companies to care for them. The Chinese healthcare sector is highly uneven, ranging from excellent to primitive, and the rising issues of obesity and other chronic illnesses means that China is open to cooperation in this sector as it sees that a universal healthcare system funded by the state would be a massive challenge. That Australia has managed to get access here before anyone else is a big advantage.

On financial services, the opportunities are also wide-ranging. Australian insurance companies are promised easier access. Australian banks are the first to be allowed to reduce their waiting time to undertake local currency trading from three years down to one. Approvals for opening branches, currently highly complex, are reduced, and the funds management sector, one where Australia has real strengths, liberalised so that local companies can offer advice to Chinese “Qualified Institutional Investors”, those who are granted the rights within China to invest abroad.

All of this looks very promising. But Australians seeking to engage with the new framework for business relations being offered need to dampen their gratitude by an acknowledgement that in almost all of the areas set out above, China has great need for international partnership for it to raise its own game. It cannot establish a good quality services and finance sector without foreign know-how and co-operation. It needs advice on outward investment, and the management of funds. Despite the generosity of the deal, therefore, there is a solid core of Chinese self-interest being looked after here.

This is not a criticism. A Free Trade Agreement, after all, should be one where both sides feel like they came off as winners. With this one, too, there is an underlying harmony of interests. China needs outside help and it needs better and more secure resource and agribusiness suppliers. Australia needs more diverse markets particularly with its largest current trading partner. Because there is a relatively simple calculation of interests involved here, the FTA should work out well. The only issue would be an Australia business community that did not want, or did not feel able, to take the opportunities being opened up through innate conservatism or simple lack of a straightforward route to get there. Government will probably need to continue educating people about this deal and promoting it. For this reason, its role is far from over.

Kerry Brown is Director of the China Studies Centre and Professor of Chinese Politics, University of Sydney.