Nation-States in an Age of Uncertainty

As the infrastructure of globalisation falters, one thing is clear: newly empowered nation-states are taking the stage. Legacies of debt and dependence will make a simple return to the past impossible, but nor is there a clear path forward. Welcome to the age of uncertainty.

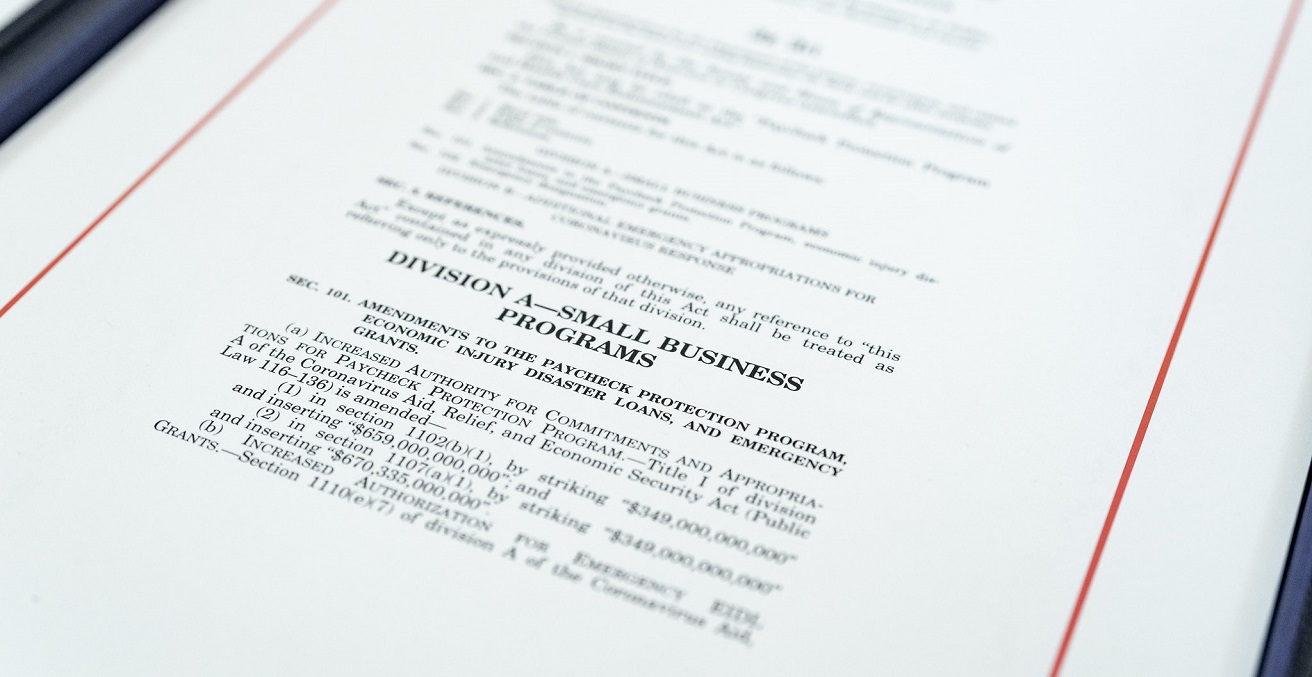

State intervention on this scale would have been unimaginable even a month before. In a globalised world, states were meant to wear “golden straitjackets”: a combination of free trade, deregulation, and small government, policed by international capital markets and the weight of sensible economic opinion. Yet as a result of this pandemic, we are watching states the world over take off their straitjackets in hope of staving off economic collapse.

Globalisation and multilateralism were coming up against headwinds even before the pandemic struck. US policy during the 1990s and early 2000s had been to integrate China into the world economy and turn a blind eye to its trade practices in return for cheap consumer goods and the hope that political liberalisation was around the corner. Trump’s bipartisan trade war is a repudiation of that strategy and a reassertion that trade must serve the national interest. And this is not just a “Trumpism.” The EU is considering carbon import tariffs to protect its manufacturing sector, even as it hardens its borders to immigrants. For high-technology and high-skill urban areas, globalisation meant new wealth, demography, and values. For those living in the West’s decaying industrial skeletons, it brought a deep sense of dislocation. Brexit and Trump were their demand that the instruments of the state mitigate or reverse the cultural, economic, and political change globalisation had become associated with.

It is too soon to say whether COVID-19 will benefit nativists or globalists. Populist leaders who promised to take back control are now struggling to maintain it. The infection curve has shone a spotlight on government competence and exposed weaknesses in democracies and authoritarian regimes alike. Central banks across the world are cooperating to preserve the international monetary system, while scientists coordinate the global search for a vaccine. Pessimists point to increasing pressure on businesses to move supply chains closer to home, especially for essential medical goods. Trump is continuing the trade war by other means with his suggestion China may have been “knowingly responsible” for the pandemic. International leadership from other quarters looks unlikely, with infighting in the EU, widespread restrictions on the export of medical equipment, and the increasing irrelevance of the UN.

Whichever political movement emerges victorious, the crisis serves as a reminder that the basic units for collective action are still a state and its people. The world leaned on government stimulus before the crisis, it is wholly on it dependent now. Across the developed world, the machinery of state has been mobilised on a scale not seen since the Second World War. This expansion has been primarily directed inwards at the citizenry. Nor are these trends likely to reverse post-pandemic. Once the immediate crisis passes, politics will spring anew from the inconsistencies and inequities in state responses. Following the Second World War, government spending in the US never returned to pre-war levels. New expectations and demands have permanently increased the role of government. Today’s calls for more resilient health systems and economic security will create a similar pressure. Even in countries where the crisis has exposed a vacuum of state power, the failure and mismanagement are only likely to strengthen the voices of those who would rebuild state capacity.

Bigger states do not necessarily spell the end of globalisation. The post-war Bretton Woods economic system showed assertive states are compatible with a structured system of trade and cooperation. Nor is globalisation as fragile as many pessimists portray. Since the 2008 global financial crisis, we have seen a plateau not a collapse, with exports as a percentage of world GDP still hovering near their 2008 historic peak of 30 percent. This pandemic will cause a serious downturn in the short run, but we must not forget how deeply integrated the world is and the collective interests to maintain it. Core economies like the UK, Germany, France, and South Korea are deeply entangled internationally, with trade-to-GDP ratios above 60 percent. Despite Trump’s isolationist posturing, the privilege of having the global reserve currency has forced the US Federal Reserve to take leadership of at least the international monetary system. What is true is that the hyperglobalisation experiment, the dream of a single model of politics and economics integrated across borders, may well be gone. It would be a mistake to see it as the only form globalisation can take. Could changes in global supply chains reshape international commerce and politics? Yes. Does that necessarily herald the end of global integration or cooperation? No.

What we require is a series of collective decisions about the future structure of global political and economic relations. Unfortunately, the possibility of a coordinated international approach – a “new Bretton Woods” conference – looks as remote as ever. Instead, we are entering an age of radical uncertainty, where much is unknown, and even more is possible. In this age of uncertainty, expect to see more of the half measures, experiments, and improvisations that have characterised policy making since 2008. As states fumble in the dark, this febrile environment will reward political entrepreneurs able to read the uncertain currents of today’s politics. Empowered states make the stakes all the higher.

The last hundred years saw liberal democratic states outlast first fascism, then communism. At the end of the Cold War, there was hope that the major problems of political and economic governance had been solved and all that was needed was a safe pair of guiding hands.

Three decades of war and economic crisis have since hollowed out this hope. Today, the future is again unknown, and history is back with a vengeance.

Lewis Jackson is an ex-management consultant moved to public policy. He graduated from the University of Sydney with First Class Honours in Government and International Relations and is doing a Masters in Public Policy and Political Economy in the Netherlands and Spain.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.