Australia’s false China choice over Taiwan

Arguments currently raging in Australia about the so-called China choice have not addressed the crucial issue about what specific concessions must be made to accommodate a rising China. Instead, debate consists of generalised statements that the US needs to provide China with strategic space by acknowledging its legitimate strategic interests.

China has identified Taiwan, Tibet and, more recently, the South China Sea as core national interests. Currently, most of Australia’s attention about China’s growing assertiveness has been focused on the East China Sea and the South China Sea.Beijing, however, has not renounced its threats to use armed force to regain what it sees as the renegade province of Taiwan. In the two Taiwan Strait crises of 1954 and 1958 the US made it clear that it would defend Taiwan, including with nuclear weapons if necessary. In 1996, Beijing held military exercises off the coast of Fujian province opposite Taiwan simulating an amphibious landing on hostile territory. America’s response was to send two aircraft carrier battle groups through the Taiwan Strait in a show of force, signifying that the US was too powerful to be coerced.Now, there is huge trade between Taiwan and China worth US$165 billion and growing by 18 per cent per annum, investment in China worth US$14 billion annually, and tourism involving 800 aircraft flights a week. These sources of ‘soft power’ have cemented a prolonged period in which the threat of force between Beijing and Taipei has been put to one side. Diplomacy on both sides of the Taiwan Strait seems to have prevailed. The question now is whether an increasingly assertive China will calculate that time is not on its side, with Taiwan becoming far too ensconced in its democratic independence.Taiwan has been off the radar screen for almost 20 years now. But as Henry Kissinger observes in his book On China, the potential for confrontation in the US–China relationship is the unresolved challenge.

The latest Pentagon report to the US Congress about China’s military power observes that preparing for potential conflict in the Taiwan Strait, which includes deterring or defeating third-party intervention (in other words, the US), ‘remains the focus and primary driver of China’s military investment’. China appears prepared to defer the use of force as long as it believes that unification remains possible in the long term. But it believes that the credible threat of use of force is essential to maintain the conditions for progress in cross-strait relations and to prevent Taiwan from making moves toward de jure independence.

China is developing formidable military forces to coerce Taiwan or to attempt an invasion if necessary. Taiwan’s security has historically been based upon the PLA’s inability to project power across the 160 kilometre wide Taiwan Strait due to natural geographic advantages of Taiwan’s defence. All of this is now changing, with a massive build-up of Chinese military forces opposite Taiwan, the loss of the Taiwanese military’s technological advantage, and rising doubts about America’s willingness to intervene given the superiority of PLA military forces in its immediate neighbourhood.

China still lacks the conventional amphibious capacity required to support a full-scale invasion of Taiwan. But it has overwhelmingly superior numbers of combat aircraft within unrefuelled range of Taiwan as well as large numbers of attack submarines, surface combatants and naval aircraft designed to achieve sea superiority. Taiwan’s own 2013 National Defence Report states that the PLA is capable of blockading Taiwan and seizing its offshore islands. As ASPI’s Ben Schreer points out, these factors have greatly complicated Taiwan’s current strategic situation because the PLA has changed the cross-strait military balance and thereby also raised doubts about the United States’ will and ability to come to Taiwan’s defence.

If China ever decides to attack Taiwan, Taipei will critically depend on US military intervention on a large scale. This would mean war with China and it would raise questions about which US allies would also come to the defence of Taiwan. Other than the possibility of logistics support by Japan, it is unlikely that any other Asian country would join America in such a conflict. And it is hard to think of any European country fighting on the other side of the world, especially given current preoccupations in Europe with Putin’s Russia. That leaves Australia being faced with the ultimate challenge in the so-called China choice.

Over the decades, successive Australian governments have quite rightly refused to respond to any questions about such a contingency. But a refusal on Australia’s part to invoke the ANZUS Treaty in such a major conflict, involving Chinese attacks on US armed forces, could well be an alliance-breaking issue.

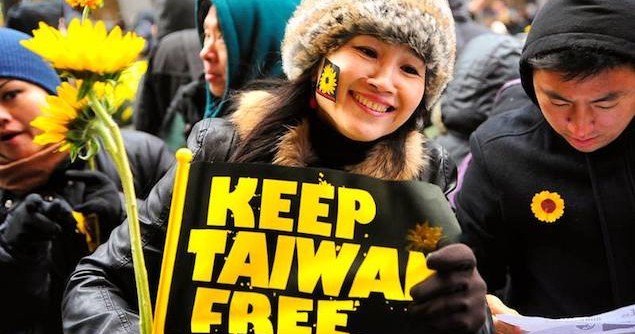

Short of such worst-case contingencies, it is important for the US and its allies, like Australia, to resist any moves by Beijing to force Taipei into becoming part of a Chinese hegemonic regional order and giving up its vibrant democracy. As Kissinger argues in his latest book, World Order, the question now is how China will relate to the contemporary search for world order. And the central issue for Taiwan’s survival, in this context, boils down to the quest for legitimacy over naked power politics.

Paul Dibb is Emeritus Professor of strategic studies at The Australian National University’s College of Asia and the Pacific. He was a guest of Taiwan’s Foreign Ministry from 9–13 September 2014.

This article was originally published by the East Asia Forum. It is republished with permission.