Japan's Abe Seeks Economic Inspiration During U.S. Visit

Summary

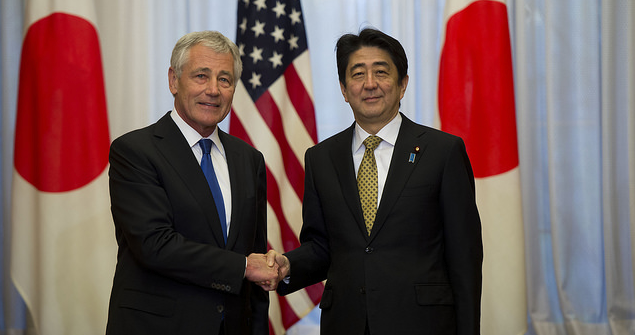

On April 26, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe will kick off what is shaping up to be a landmark visit to the United States. After meeting with U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in Boston on Sunday, Abe will travel to New York and Washington for three days of meetings. The visit will culminate in a summit and state dinner hosted by U.S. President Barack Obama on April 28 and a speech before both houses of Congress the following day. Equally suggestive, but far less noted in mainstream coverage of the visit, is Abe’s post-Washington schedule. From April 30 to May 3, the prime minister will tour Silicon Valley, San Francisco and Los Angeles in search, according to the Japan Times, of “inspiration” for improving his plan to revive the Japanese economy, known colloquially as Abenomics.

Abe’s U.S. itinerary reflects the intimate relationship, symbolic and real, between his domestic and regional agendas. It also points to the central role Japan’s relationship with the United States plays in achieving its economic goals as well as its regional security and diplomatic objectives.

Analysis

Abe’s meetings in Boston, New York and Washington attest to Japan’s struggle to break free from the legal and practical constraints that formed the cornerstone of the post-World War II U.S.-Japanese partnership. Japan desires to play a more proactive and autonomous role in shaping regional security and political dynamics across Asia, especially concerning China. To this end, foreign and defense ministers from Japan and the United States will announce the approval of revised guidelines for U.S.-Japanese defense cooperation on April 27. The revision will formalize U.S. support for Japanese collective self-defense and point to the ratification of collective self-defense and related legislation in Japan’s Diet sometime this summer.

Abe’s U.S. visit also speaks to the strategic and practical aspects of his efforts to resuscitate Japan’s economy. The 12-country free trade agreement known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership will feature prominently in Abe’s discussions with Obama and his speech to the U.S. Congress on April 29. The U.S. Senate Finance Committee passed presidential “fast-track” approval of the agreement on April 15, though full congressional support for the fast-track measure is pending.

For Abe, the agreement’s significance is manifold. At the broadest level it offers a multilateral vision and foundation for U.S. and Japanese efforts to contain a rising China by providing an institutional framework for economic and diplomatic cooperation among member states. Simultaneously, it adds an element of international legitimacy and urgency to Abe’s efforts to push through politically sensitive structural social and economic reforms at home, the “third arrow” of his Abenomics economic revival program.

Moreover, there is a natural synergy between the U.S. demand that Japan open long-protected markets for goods like agriculture — a key component of Japan’s Trans-Pacific Partnership accession talks — and Abe’s efforts to break agriculture and other industrial lobbies’ electoral power and legislative influence. Diminishing that influence would enable Japan to attract more foreign investment. It would also subject the country’s economy to greater outside competition, improving productivity and promoting growth across the economy.

Abe’s decision to spend the latter half of his U.S. visit in California is perhaps no less significant than his meetings on the East Coast, though the specifics of his itinerary there are unclear. Since coming to office in 2012, the Abe administration has repeatedly stressed the importance of cultivating a cutting-edge and innovative computing industry as an heir to the advanced manufacturing and electronics hardware-based model that propelled post-World War II Japan’s economic “miracle.” To this end, the administration has put in place measures to ease domestic startups’ access to capital and to encourage risk-taking among Japanese entrepreneurs.

For Abe, these efforts are part and parcel not only of his short-term goal of reviving economic growth and improving full-time employment, especially among younger workers, but also to ensure Japan’s continued technological edge over neighboring China and South Korea. In an era when the computer is fast replacing the assembly line as the organizing principle of security and warfare, physical or cyber, the advantages of cultivating a world-class computing industry goes beyond economic interests.

Abe’s week in the United States will reinforce the sense that East Asia’s core geopolitical gears are shifting. China is on the precipice of what is likely to be a decade of tremendous social, political and economic stress, while Japan appears poised to further strengthen its role in regional economic, military and political affairs. But U.S. and Japanese domestic politics, along with factors like Japan’s high and rising levels of underemployment amid a shrinking workforce, will continue to curb the Abe administration’s efforts to realize its vision for a Japanese national revival. Japan may indeed attain such a revival and even break from the post-World War II Japanese political and economic order. But that does not mean Abe’s efforts represent that revival. They may merely be a preface.

This article was originally published by Stratfor Global Intelligence. It is republished with permission.