Chile: A Victim of Its Success?

Chile was once an oasis of tranquillity in Latin America that has suddenly erupted into an outbreak of people on the streets on a scale not seen since the end of the dictatorship 29 years ago. What went wrong in Chile?

It all began as a result of a hike in the subway fare. The price went up from 800 to 830 Chilean pesos during peak hour (an increase equivalent to 4 percent, equalling 60 cents, to a total of AU $1.65 per ticket) which led to mass protests and the declaring of a state of emergency by the government. The next day, the increase to the subway fare was reversed, but the protests escalated.

Often noted as an oasis of tranquillity in Latin America, Chile suddenly erupted in mass unrest on a scale not seen since the end of the dictatorship almost three decades ago. So far, the protests have involved one million protesters, 2,410 arrests, almost 600 injuries, at least 20 deaths, as well as AU $2 billion in losses to Chilean businesses. Ongoing protests scattered around the world in Hong Kong, Lebanon, Iraq, and now Chile have shared the same central themes – inequality and resistance to government actions.

The unexpected unrest has resulted in the government deciding to cancel two high profile global summits: the APEC trade forum and the COP25 on climate change which were scheduled to take place in November and December respectively. Chilean President Sebastian Piñera framed the move as prioritising Chileans over all else, saying “a president must always put his compatriots above all else.”

Longstanding Grievances

In Chile, the fare increase was just the tip of the iceberg. Inequality has taken centre-stage in the debate in recent days, but other issues such as the rising cost of living, gender inequality, climate change, government ethics, and poorly performing public institutions have hovered in the background.

The minimum wage in Chile is 300,000 pesos (AU $605) a month, while, according to the Instituto Nacional de Estadisticas, half of the workers in Chile receive a salary equal to or less than 400,000 pesos (AU $810) a month. With this salary, protesters claim that the rise in the subway fare was inconceivable and unacceptable. For minimum wage workers, public transportation can constitute 15-20 percent of their wages.

In response, over the last few days, Piñera has fired his entire cabinet and announced an overhaul to the pension, transport, and health systems. He has also reduced the salaries of congressmen and public officials which, along with a reconstruction package, is bound to stimulate economic growth. Both the government of President Sebastian Piñera and the political opposition agree that the current administration reacted late to the demonstrations. The administration has been criticised for not providing a clear explanation about the fare hike, which demonstrates a lack of empathy with the people’s problems.

Historical, Economic and Political Context

The Social Panorama of Latin America report prepared by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) describes that in 2017, the wealthiest 1 percent of the country possessed 26.5 percent of the wealth, while 50 percent of lower-income households accessed only 2.1 percent of the country’s net wealth.

Nevertheless, Chile has the lowest level of inequality compared to all other Latin American countries. Even if one is born into the lowest class, the likelihood of progress out of poverty is one of the highest compared to other countries in the region. Average actual incomes have been rising for the past 25 years, but wealth distribution is markedly low. This is suggested by Chile’s Gini coefficient of 0.50, one of the highest coefficients in the world for inequality. It is a legacy of the military dictatorship of the 1970s and 1980s. During that time, inequality rose quickly because real wages sank under the pressure of high inflation, unemployment, and political repression against civil society and trade unions.

In the past 29 years of Chilean democracy, there has only been only six years of right-wing government rule. Today’s mobilisation may be more a result of frustrated expectations of a progressive pace of growth that Chile had experienced in the past, but which has stagnated in recent years.

Piñera Takes Control

Two years ago, Chileans voted for change in support of Piñera after the Bachelet government. Piñera had previously been recognised for his ability to generate jobs and improve the economy, his greatest achievement during his first term as president from 2010 to 2014. People wanted similar levels of economic growth, but so far, the economic reality has fallen short of the expectations of Chilean citizens, especially the youth.

Other than the battery of reforms already detailed by Piñera, the administration has announced that it will address longstanding issues, including increasing pensions; a guaranteed minimum wage; limiting healthcare costs; raising taxes on the wealthy and the reversal of a planned increase in the price of electricity.

Although 80 percent of people polled thought his proposals were insufficient and the protests persist, President Piñera is endeavouring to placate the unrest. Partially because of splintered political parties and the fact that there is not one actor representing the protesters, the government is left with no specific demand apart from blanket calls for social justice and reform. Commentators noted that there have not been any promises on education, which was a subject of protest in 2006 and 2011.

Outlook

Despite these circumstances, Chile is a country that will continue to stand out in Latin America for its stability and solid institutions. The global environment is driven by geopolitical, economic and demographic shifts. When a tipping point is reached, change can occur rapidly, creating both challenges and opportunities. Though security forces tried to disperse crowds with water cannons, the protesters chanted, “The people united will never be defeated.” The governor of Santiago, Karla Rubilar, wrote on Twitter, “today is a historic day.”

Observers have posited that Chile may be a victim of its success; a country that supersedes local standards but falls short of the collective aspiration of Chileans to achieve much more. It will take time for the policy measures aimed at addressing inequality to take effect, but the process of normalisation became evident today with fewer protesters on the streets. Chile will once again figure out how to solve its problems and move on, strengthening itself as a standout country in Latin America.

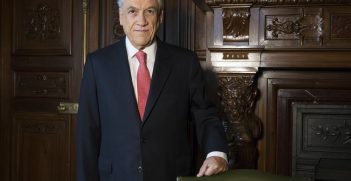

Fernando Rodriguez is the General Manager (South America) for Swann Global and is based in Santiago, Chile. He holds a degree in economics and a Master’s degree in International Trade from Monash University in Australia.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.