Securing Australian Interests: Canberra’s Struggle to Redefine its Economic and Strategic Relationship with China

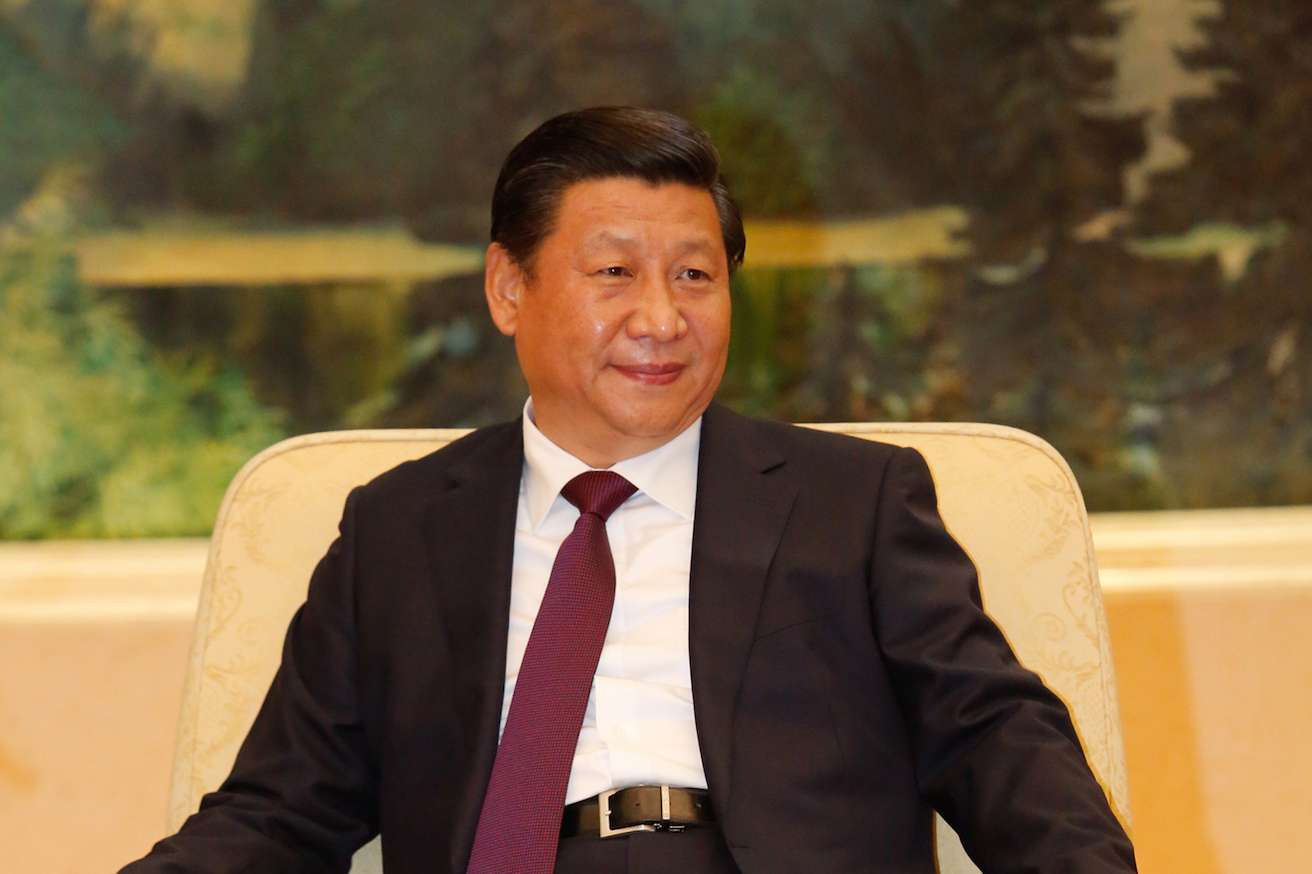

The rise of China is unsettling nations in the region, not least Australia. Canberra needs to reassess its relationship with Beijing to ensure that it does not become a passive pawn in Xi Jinping’s power game.

Liberal MP Andrew Hastie has been condemned for a controversial opinion piece he recently published on the Sydney Morning Herald. Most of criticism is linked to the perception that Hastie’s goal has been the one of linking Xi Jinping’s China to Nazi Germany. In particular, Hastie has been accused of comparing the rise of China as an unnoticed existential threat to Australia, similar to the one that Hitler’s Germany has been to France.

The People’s Republic of China was the very first country to react to this opinion piece describing it as “extreme.” Through its embassy in Australia, Beijing immediately rebuked Hastie emphasising the dangers connected to the spread of a “detrimental rhetoric on ‘China threat’” nurturing hazardous ideological biases and a Cold-war mentality.

Hastie’s comments sparked a lively debate in Australia as well, where ministers, analysts, and commentators started asking themselves if the liberal MP had made his controversial views public just to get the attention of the press, without considering the implications of his critical remarks on the already delicate relationship between Australia and China. It could also imply that he was right to ring another bell on this issue, warning that Australia’s greatest vulnerability lies in the way the country will decide to interact with China.

By looking at the original opinion piece, Hastie’s message appears as more subtle than a basic comparison between China’s and Nazi Germany rise. Media have attacked Hastie for his inappropriate connection between Xi Jinping’s China and Hitler’s Germany, but the assessment he made was focusing on the essence of the threat they represent for their neighbours, not on the nature of their political system.

The liberal MP’s commentary emphasised two points: first, that the idea that economic liberalisation would have naturally led China towards democratisation has played for decades the role of Australia “Maginot Line.” The Maginot Line was the immense fortification France prepared to respond to the German threat and that ended up contributing to its own defeat during WW2, by making the military too complacent and defence-minded. If the idea that economic liberalisation represents Australian Maginot Line to respond to the Chinese threat is based on the conviction that China one day will stop representing a menace because it will transform into an open and reliable democracy, then Australia has fooled itself as the Chinese political system will never change.

The second point that Hastie stressed is that as the French failed to appreciate the evolution of mobile welfare and decided to build a massive fortification such as the Maginot Line on the run-up to WW2 grounding on their tragic experience with trench warfare during WW1, so too is Australia is now failing to correctly assess how mobile its authoritarian neighbour has become. As a consequence, it has not been able to finalise an effective strategy not only to counterbalance China, but also to secure Australian interests vis-a-vis its Asian neighbour.

Is Hastie’s assessment on China’s threat right or is he also a victim of the new anti-China rhetoric that is emerging in Australia? In 1991, former American president Richard Nixon told his biographer: “within twenty years China will move to democracy.” He then explained the need for America to be patient: “You can’t rush them. The Chinese look at history and the future in terms of centuries, not decades, the way we do, because they are so much older as a culture.”

The myth that liberalisation would bring democracy to China has been a very popular one for decades. The basic idea associated with it was that after spreading into the Chinese economy by making the country richer, liberalisation would “infect” the society, pushing it to breathe the advantages of political liberalisation. This new appealing dream would have inevitably persuaded the Chinese people about the need of a radical regime change.

Once and for all, China has proved this myth totally wrong. However, Hastie is also wrong because presenting economic liberalisation as the western Maginot Line vis-a-vis China is another false comparison. Economic liberalisation was never meant to contain China or to protect the rest of the world from a Chinese invasion, rather to transform the country into something the Communist Party has never been interested in considering: western liberal democracy. This huge misunderstanding is the biggest mistake all western countries have made so far in deciding how to structure their relationship with Beijing.

Their convinction that one day China would have become a democracy and that, as a consequence, it would have been able to fully integrate in the existing international system pushed Australia and many other countries to accommodate Beijing’s rise and interests while taking advantage of the huge opportunities related to its economic liberalisation.

Today, and this brings us back to Hastie’s second point, with president Xi Jinping confirming that this prediction is wrong, foreign countries have found themselves in the very difficult position of balancing sovereignty and prosperity, security and trade with a nation that has become completely unpredictable.

The real problem many countries are now facing, and Australia is one of them, is that while naively waiting for China to democratise and become a reliable international actor, they have developed an irreversible economic dependence from Beijing. The United States is the only nation that has maintained the capacity to use maximum pressure and a strategy based on continuous economic and political provocations to try to rebalance their dangerous dependence from China. Hastie is right in suggesting that almost every strategic and economic question that Australia will be facing in the coming decades will be refracted through the current geopolitical competition of the US and the PRC.

If this is the case, can Australia generate a genuine internal debate grounded on its own interests? It is true that bipartisan support was secured to a new law countering espionage, foreign interference and influence in Australia, and that the country found an agreement on how to keep its 5G network free from Chinese interference. However, this is not enough to protect the country while dealing with the new vision of the world Xi Jinping is pursuing.

The real problem is that as long as the geopolitical competition between the US and China will not be over, Australia will not be in the capacity to autonomously decide in which direction to go. By choosing between Washington and Beijing, Canberra has a lot to lose. But the dream of maintaining a balance and profitable relationship with both is not realistic any more. The country needs to discuss what it wants to do in the interest of Australia and of Australians. This is the most important message that Hastie tried to highlight in his opinion piece: if Canberra will continue passively waiting, it will relegate itself to an even worse position, becoming a passive pawn of Xi Jinping’s game.

Dr Claudia Astarita was educated at the University of Bologna and has a PhD from the University of Hong Kong. She was a non-resident Fellow in the Asia Centre in the University of Melbourne and is currently based at Sciences Po–Lyon, France.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.