The Moscow-Beijing Relationship: Increasingly Asymmetrical and Resilient

With the Sino-Russian relationship ostensibly at its best time in history, it is by no means a relationship between equals.

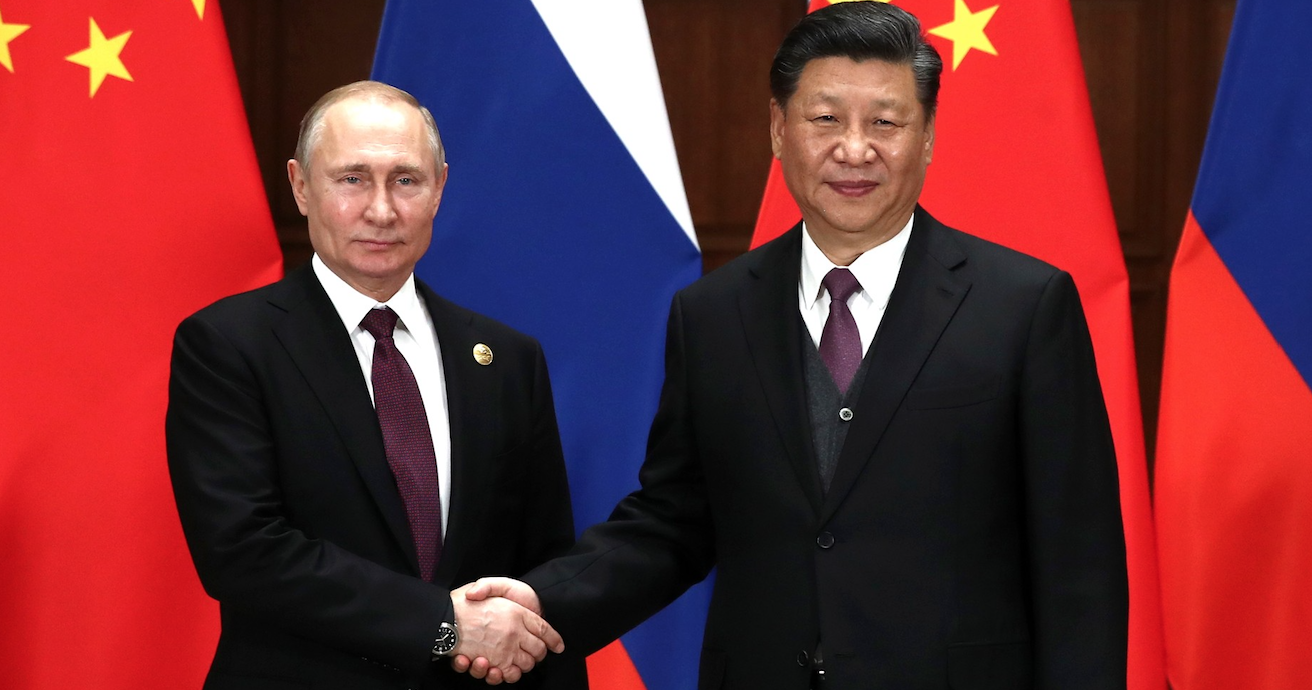

The June visit of China’s leader Xi Jinping to Russia brought about another elevation of Sino-Russian relations. Their “comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination” gained an linguistic extension: becoming a partnership “in a new era.”

This move is symbolic in two respects. For the first time ever, China’s strategic partnership with Russia is now formally distinct from several dozen other PRC strategic partnerships.

At the same time, however, the new slogan shows how Chinese politics has been increasingly defining the language of Sino-Russian relations. “A new era” characterizes every aspect of Xi’s policymaking. While the Kremlin’s gesture recognizes Xi’s claims to a unique place in the PRC’s history, it also serves as a reminder of the growing asymmetry between the two powers.

Yet neither this asymmetry nor historical obstacles to cooperation have weakened Sino-Russian ties: the relationship turns out to be unexpectedly resilient.

Ever Closer Cooperation

Shared aversion towards numerous features of the post-Cold War liberal international order and US unilateral policies has provided a solid foundation for Sino-Russian cooperation. Western promotion of democracy, readiness to intervene militarily in the face of humanitarian crises as well as the defence of human rights have generated particular animosity in Moscow and Beijing. It would however be a mistake to reduce Sino-Russian ties to joint anti-US or anti-Western posturing. Sino-Russian cooperation has gained in substance for the last decade, especially in military, energy and economic realms.

Regular land and naval exercises, conducted by both militaries since 2005 and 2011 respectively, have been crowned with the Chinese participation in the Vostok-2018 exercises. A Chinese brigade took part in the largest military drills in Russia since the 1980s. As the exercises required three thousand Chinese troops to be transported across Russia, both states had to master practical details of international military collaboration. Secondly, previous editions of the Vostok exercises, in 2010 and 2014, were interpreted as implicit warning signals sent towards China, confirming the Russian military’s robustness and preparedness. China’s participation in the current edition testifies to the evolution of Russia’s threat assessment and subsiding fears of China’s rise. The Vostok-2018 exercises were followed by annual naval drills, Joint Sea, staged in the first half of 2019 in the Yellow Sea.

In the energy realm, the natural gas “leg” of cooperation began to catch up with the well-developed collaboration in the oil sector. While Russia has been China’s number one crude oil supplier since 2016, having surpassed Saudi Arabia, in 2018 Russian exports broke a record. Russian companies provided their Chinese counterparts with 67 million tons of oil, or one-fourth of total exports. China has also emerged as a top foreign investor in the Russian LNG sector, having added a stake in the new Arctic-2 LNG project to already possessed shares in the Yamal-LNG project. That way Beijing not only secured additional supplies but also strengthened the foundations of Putin’s political economy: Novatek, the company behind the project, is owned by people said to be close to Vladimir Putin. On top of this, Power of Siberia, a long-expected gas pipeline, is to come online towards the end of 2019. Even though the initial volume is going to be relatively small, newly explored gas resources in Eastern Siberia are increasingly tied to the Chinese market and fenced off from other potential customers.

Economic cooperation, which was always considered the Achilles’ heel of the Sino-Russian relationship, seems to have finally advanced. Last year, bilateral trade turnover reached US $108 billion. According to Russian officials, Chinese companies are currently implementing 30 investment projects with the value of US $22 billion. Even cross-border cooperation in the Russian Far East took off, with US $3.5 billion of the Chinese investments being implemented and the first ever bridge over the Amur River completed.

Dangerous Reefs …

More substantial cooperation does not mean the absence of challenges. When looked at from a decade-long perspective, there were a number of issues that might have derailed the relationship. The growing power gap between the two states is certainly the most significant in this regard.

The increasing asymmetry between China and Russia threatens the notion of an equal partnership. This asymmetry manifests itself on a number of levels. It is most conspicuous in terms of material power. China’s economy is seven times larger than Russia’s. China’s military budget is three times bigger, even though Beijing maintains military expenditures below the two percent of GDP level, while Moscow has spent between four and five percent for the last couple of years.

The bilateral relationship has different weight for the two sides. For Moscow, China has emerged as the most important partner across a number of areas. China’s relations with the external world are much more balanced. This has been evident in a talk by a Chinese diplomat-turned-scholar that I had an opportunity to listen to at the University of Malaya last month. Discussing China’s number one foreign policy problem — a trade war with the United States — he did not mention Russia once. This points to one of the key limitations of the relationship. While Moscow can offer geopolitical and strategic support to Beijing, it cannot do much to help China in economic terms. Russia cannot provide a market for Chinese products banned from the United States, offer technologies Chinese companies are after or become a secure place to invest trade surpluses.

Both states’ activities in each other’s backyards constitute another dimension of the asymmetry. China has managed to establish itself as Russia’s peer in Central Asia and has increased its engagement in the Arctic, considered by Moscow its “strategic frontier.” Against this backdrop, Russia’s efforts in East Asia have mostly been futile. Moscow has not managed to balance its relations with China by developing ties with other Asian states and has been forced to follow in Beijing’s footsteps. Competing regional projects in Eurasia illustrate the asymmetry even better. Whereas China’s Belt and Road Initiative has been gradually implemented, Russia’s Greater Eurasian Partnership is an exercise in mere status-seeking, not a tangible vision of regional cooperation.

… And Surprising Resilience

Against this backdrop, the resilience of the relationship can be explained by a constellation of several factors that have created a fertile ground for Sino-Russian ties. The US primacy and strategic considerations in Moscow and Beijing are without doubt one such factor. Domestic politics is another. Cooperation strengthens both regimes’ internal security and facilitates the exchange of authoritarian “best practices.” At the same time, dominant players in both states benefit from close but opaque ties and can promote their parochial interests behind the curtain of “national interests.” Growing normative convergence against the West, which is mostly limited to negative aspects, constitutes the third building block. Russia and China agree on what they dislike about the liberal order, while disagreeing on economic globalization, global populism and protectionism.

The final question is whether this relationship can evolve into a fully-fledged alliance. Apart from political declarations that explicitly deny it, one serious obstacle is both states’ unwillingness to support each other’s assertive and aggressive moves, such as towards Ukraine or in the South China Sea. At the same time, we witness expanding ties between both establishments that in a long-term perspective can transform the Sino-Russian relationship.

Dr Marcin Kaczmarski is a lecturer in the School of Social & Political Sciences, University of Glasgow. He is the author of Russia-China relations in the post-crisis international order (Routledge 2015).

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.