Look Who Made the Top UN Job

After the sixth round of informal straw polls in the UN Security Council, on 5 October (New York time) all UNSC members came out together to announce agreement on a new secretary-general for the United Nations: Antonio Guterres.

The final indicative vote for him—the first in which different coloured straws were used for the five permanent members—was 13 yes, nil opposed, and two undecided. Following this the Council would meet at 10am on Thursday to vote formally with the most likely scenario that he would be chosen by acclamation and the General Assembly (GA) would ratify the selection by affirmation.

Two years ago, another former senior UN official and I began speculating on the attributes of the next secretary-general (SG) after Ban Ki-moon. I remarked that of all the candidates I could think of, my first choice would be the then UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Guterres. I suggested to my Portuguese colleague then that he should encourage his government to begin thinking of the idea long-term in order to explore the prospects and prepare the ground. Prime Minister of Portugal from 1995–2002 (and as such the first ex-PM to be chosen SG), in 2005 Guterres became the UNHCR for 10 years and his reputation within the UN system was quite high during the time I was still a UN official (until April 2007).

I met him once (or maybe twice) after that in a relatively small and intimate setting and was impressed by his performance. Anecdotal evidence confirmed that his reputation among most governments and civil society remained very high for competence, integrity, values and willingness to speak out in defence of those who lacked voice but needed support. These qualities were even more starkly in demand and evident in the final two years of his tenure as the refugee crisis hit Europe. Not surprisingly, therefore, I am pleased with the outcome.

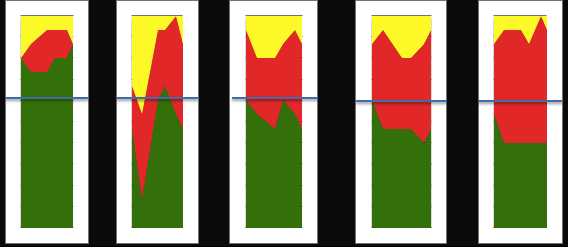

There are four very impressive features about his selection. First, he led the race from start to finish in the six rounds on 21 July, 5 and 29 August, 9 and 26 September and 5 October (see the illustrative chart). Second, in every poll his vote remained above the qualifying threshold of 9 of the 15 UN Security Council (UNSC) votes (indicated by the bar in the chart). Of the 13 other candidates, Slovakia’s Miroslav Lajcak, Serbia’s Vuc Jeremic and Bulgaria’s Irina Bokova managed to reach the threshold once or twice but not maintain it. Third, despite his forceful advocacy for the UN refugee regime and compassionate advocacy on behalf of the huddled masses of refugees seeking shelter in Europe, Guterres remained courteous and collegial enough throughout that he never irritated the Europeans, or else Britain and/or France could have vetoed his candidacy. Fourth and even more importantly, despite being a former PM of a NATO country and not being East European, he managed to avoid a veto from both Russia and China. (Russia is believed to be one of the two who expressed no opinion on his candidacy in the 5 October poll.)

There are also four other instant takeaways from the exercise.

First, this year’s was the most transparent and inclusive selection process in UN history. Denmark’s Mogens Lykketoft, who as president of the 2015–2016 GA initiated most of the key innovations, believes this was a game-changing process that will be difficult to reverse. The UNSC president and Lykketoft sent out a joint letter last December seeking candidates; asked the officially nominated candidates to provide vision statements that were uploaded to a public website; and organised interactive dialogues between the candidates and UN member states and civil society. Having read them in April, a former UN colleague and I concurred that Guterres’ vision statement was the best of all: concise, clear, visionary yet within the limits of pragmatism. Those who wish to know more about the next SG should read that document even now. As Lykketoft explained, the process allowed all member states to learn about the candidates’ personality, their priorities and the challenges facing the UN over the next five to ten years. It also enabled the GA to influence UNSC perspectives on the several candidates.

Another possible benefit of the more transparent process might prove to be that Guterres has secured the post without having to negotiate side deals with the permanent five (P5) members of the UNSC, such as committing key posts to their nominees. If so, it would leave him free to appoint the best candidates to the UN’s most consequential positions.

Second, the regional criterion remains important but for any region to succeed, it must unite behind one candidate from the start. Nine of the 13 total candidates were from Eastern Europe, which badly split their votes and ensured someone else got the job. But it is still a European, confirming that while the rationale for the UN regional groupings was primarily geopolitical in origin, the groupings have remained the same while geopolitics has moved on to render them obsolete.

Third, the gender criterion was relevant for the first time and female candidates outnumbered men, but did not prevail, for two reasons. There were again too many candidates—7 of the 13—and gender was never going to be the sole criterion.

Fourth, many candidates clearly possess a remarkable capacity for stubborn self-delusion. It would have been better after the first three rounds for all candidates who had failed to cross the 9 vote threshold to withdraw, producing a cleaner process and outcome thereafter.

Finally, although the process was more transparent and inclusive than ever before, it was far from perfect. Instead of merely trying to influence the vote in the UNSC, the GA must reclaim a formally co-equal process and thereby return the SG to being the symbolic representative of the entire international community, not subservient to the P5. Because changing any system is almost impossible once an election begins, the GA should turn its attention to this task as soon as practicable. Otherwise the cycle will repeat endlessly.

Six Security Council straw polls for 5 of 13 candidates next Secretary-General, 21 July–5 October 2016  Antonio Guterres Miroslav Lajcak Vuc Jeremic Irina Bokova Helen Clark

Antonio Guterres Miroslav Lajcak Vuc Jeremic Irina Bokova Helen Clark

Green = encourage; red = discourage; yellow = no opinion. The horizontal bar indicates the threshold of 9 of the 15 UNSC votes needed for election, including no dissenting vote of a permanent member.

Professor Ramesh Thakur, a former UN Assistant Secretary-General, is professor in the Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.