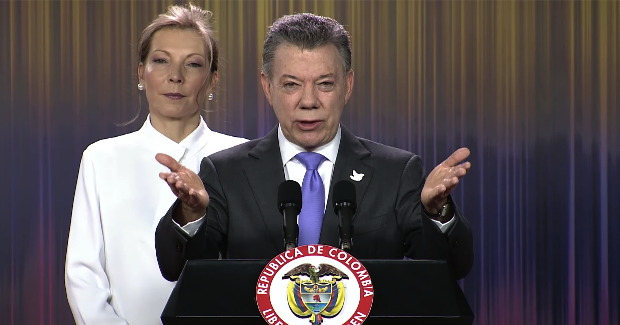

Is Santos' Nobel Peace Prize Premature?

The Nobel Peace Prize Committee announced this week that the winner for 2016 is Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos. Santos has been recognised for his efforts to end the country’s more than 50-year civil war, which has cost the lives of at least 220,000 Colombians and displaced close to six million people. But with the peace process still incomplete, some are asking whether the prize is premature.

President Santos negotiated with the leader of the chief party behind the civil war, FARC, Rodrigo Londoño, also known as Timochenko, to reach a historic peace accord on 24 August. However, when the peace accord wasput to the Colombian people in a referendum on 2 October, it was unexpectedly and narrowly defeated. The defeat of the referendum does not mean that the population does not want peace, just that the specific agreement was not sufficiently attractive to a clear majority and was seen by some as making too many concessions to the FARC. The Nobel Committee emphasised the importance of the fact that President Santos is now inviting all parties to participate in a broad-based national dialogue aimed at advancing the peace process. Even those who opposed the peace accord have welcomed this new dialogue.

The decision by the Peace Prize Committee has created controversy as some members of the international community have suggested that it is premature. The Nobel Peace Prize is one of five types of prize awarded by the Nobel Committee under the conditions of the will of Alfred Nobel who died in 1896. The Peace Prize is given to the person who “shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses“. The selection committee is appointed by the Norwegian Parliament and the prize consists of a medal, a diploma and a monetary prize. The Nobel Peace Prize can be awarded to an organisation, or group of organisations as well as an individual.

Changing nature of war

The terms of Nobel’s bequest reflect the historical context and are naturally enough framed in the ideas of war and peace that prevailed in his time time. Nobel saw war as a phenomenon that occurs between nation states, whereas today civil war is more frequent. This creates a challenge for the selection committee as Nobel specified “standing armies” rather than rebel or guerilla forces and in recent years the committee has stretched the definition of war to match contemporary realities. For example, last year’s prize was awarded to the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet for its initiatives to contain escalating civil strife. The Tunisian General Labour Union took the lead in creating an alliance with its historic adversary, the Tunisian Confederation of Industry, Trade and Handicrafts. Two other well-established and respected groups, the Tunisian Human Rights League and the Tunisian Order of Lawyers, also entered into the process. The Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the Quartet for establishing an alternative peaceful political process at a time when the country was on the brink of civil war.

Qualities of Peace Makers

Juan Manuel Santos Calderón was born on 10 August 1951 in Bogotá, Colombia. Santos attended a private school in Bogotá before enlisting in the Colombian navy. He studied in the US and England and was deputy director of El Tiempo newspaper before serving in government. In making this year’s announcement the Nobel Committee expressed admiration of the tenacity shown by President Santos. His ability to keep going despite apparent failure, his willingness to enter into dialogue with opponents, his leadership in inspiring hope that an armed struggle can be transformed into a political process make him a worthy candidate.

The autobiographies of Nobel Peace Prize winners suggest that the key strengths of those who win the prize are the capacity to think dialectically, that is, in a manner that considers and creatively reconciles conflicting viewpoints, as well as the ability to endure a great deal for the sake of their beliefs. Santos’s personal qualities are ones that he shares with previous laureates and certainly make him a worthy candidate. In particular he has redefined the ‘war on drugs’ in a way that challenges the consumer countries to take more responsibility.

The committee noted though, that its intention is not just to award an individual prize but also to encourage all those who are striving to achieve peace, reconciliation and justice in Colombia. Therefore highlighting their intention to pay tribute to the Colombian people who, despite great hardships and abuses, have not given up hope of a just peace, and also to all the parties that have contributed to the peace process.

Superficially there seem to be similarities to last year’s award, but a key difference is that the prize is made to an individual rather than shared. It is probable that the committee does not want to set a precedent of awarding the prize to guerilla forces and so the FARC leadership is subsumed under the recognition of the role of “all parties”. However, in the past violence has not solely been the prerogative of the guerrilla forces.

Is the award timely?

Suggesting that the award is premature implies that there is an ideal time frame. Nobel did not, in the terms of his will, specify a period of time and in some cases, such as in that of Kofi Annan in 2001, Shirin Ebadi in 2003 and Wangari Maathai in 2004, the award seems to be made in recognition of a lifetime of work. In other cases, such as the selection of Barack Obama in 2009 and the Tunisian Quartet last year, the decision seems to be much more in terms of current events.

This year the aim in awarding the prize is explicitly current and interventionist, hoping to influence and reinforce the peace process. But intervention carries a risk, as interventions can always have unintended consequences. Often peace processes are conducted quietly, away from the media spotlight, for good reasons. The peace process in Colombia is delicately balanced and some commentators suggest that opposition to the peace process has been in part fuelled by the envy of rivals who don’t want President Santos to succeed.

In a generous and tactful move Santos has deflected some grounds for jealousy and pledged to donate the prize money to victims of violence. Let us hope that the Peace Prize serves to endorse and reinforce the peace process, for the Colombian people have suffered enough and peace will provide the stability necessary to address the ongoing social and economic problems such as poverty and the drug trade.

Professor Diane Bretherton is adjunct professor at the School of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Queensland. Professor Bretherton has published many works and is a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of the Journal of Peace and Conflict.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.