Nigerian Elections 2019: Entrenching Democracy?

After an initial postponement, Nigeria’s presidential elections were held on 23 February. Despite some outbreaks of violence, the relatively unmarred re-election of President Mohammadu Bahari suggests democracy is starting to take hold in the country.

Since the return of democracy in 1999 after 16 years of military dictatorship, Nigeria has held six rounds of presidential elections. Although there have been different perspectives on whether the elections have been free and fair, the fact elections have been held every four years since 1999 is an indication that the country’s democracy is developing.

During the 2019 presidential election, security and the economy were the key issues which dominated the campaign. For over a decade, Boko Haram (the terrorist group based in the Northeastern region of Nigeria) has ravaged several parts of the country. More recently, conflicts between farmers and herdsmen have been on the increase resulting in thousands of death. Although the incumbent government recorded substantive success on the war against terrorism in the first two years of its administration, the emergence of a Boko Haram splinter group called the Islamic State in West Africa in 2016 has added to the security challenges facing the country. The group claimed responsibility for 23 attacks in West Africa between August and November 2018, killing at least 600 soldiers and thousands of civilians.

The Nigerian economy was also a source of concern for voters. The economy shrank by a third between 2014 and 2018, with GDP dropping from US $569 billion to US $376 billion. The main opposition candidate and former vice-president promised to revamp the economy and provide jobs for the millions of unemployed youths in the country. But despite running a spirited campaign, the incumbent president won a landslide victory. A result the opposition has already rejected.

Analysis of presidential results

The 2019 elections featured 73 presidential candidates. But the real contest was between the incumbent President Mohammadu Buhari of the All Progressives Congress (APC) and the former Vice President Atiku Abubakar, who is known by his first name and contested on the platform of Peoples Democratic Party (PDP). While the PDP is the only party in Nigeria to have remained intact since 1999, the APC is an amalgamation of several parties, including the Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), All Nigeria Peoples Party (ANPP), Congress for Progressive Change (CPC) and some other smaller parties. The APC was formed in February 2013 to compete with the PDP in the 2015 elections. Since the formation of the APC, which eventually defeated the PDP in the 2015 elections, both parties have dominated the Nigerian polity.

The 2019 presidential election was deemed to be a close contest but President Buhari won by a large margin, polling 56 percent of the votes cast. Despite the perceived popularity of Abubakar, three key issues accounted for the loss of the PDP candidate. First, the privatisation agenda of the former vice-president was not well taken by Nigerians. Atiku promised to create jobs and sell the country’s oil corporation, the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation. While selling the highly inefficient corporation might be a good option for the country, the track record of the former vice president created doubts in the minds of most Nigerians. Atiku was previously responsible for the partial privatisation of the country’s electricity sector, which has remained moribund. It was also rumoured around the country that he would sell the country’s prized asset to his associates. This forced Atiku to have to debunk the claim during several campaign interviews.

Second, political calculations – especially in the southwest region of the country – worked against the former vice-president. Since 1999, when Nigeria returned to democracy after 16 years of military rule, presidents have been constitutionally granted a maximum of two four-year terms. Additionally, there has been a “gentlemen’s agreement” between power brokers that the presidency will alternate between the north and south every eight years. Although this is not enshrined in the constitution, power has passed between the north and south since 1999. President Buhari, a northerner, had already completed his first four-year term. As such, there were concerns that voting for Atiku, who is also from the north, could potentially disrupt the convention of alternating power between the north and south of the country. Many southerners feared that if Atiku won and then later pursued a second term, they could be faced with 12 consecutive years of northern rule. This assumption pitched many voters from the south against Atiku.

Third, the anti-corruption stance of President Buhari, coupled with corruption charges against Atiku, played a significant role in the elections. Former President Olusegun Obasanjo made several corruption allegations against Atiku, his former vice president. In his book My Watch, Obasanjo wrote that what he did not know about Atiku was his “propensity to corruption, his tendency to disloyalty, his inability to say and stick to the truth all the time, a propensity for poor judgment, his belief and reliance on marabouts, his lack of transparency, his trust in money to buy his way out on all issues and his readiness to sacrifice morality, integrity, propriety truth and national interest for self and selfish interest.” It is believed that this characterisation by his former boss, worked against the candidacy of Atiku during the elections. President Buhari, on the other hand, is seen by many Nigerians as “willing” to curtail corruption in the country. This worked in his favour and most likely won him a second term.

Free and Fairer Elections?

The PDP was quick to condemn the elections with Atiku describing the presidential election as the “worst in 30 years.” Although incidents of election-related violence around the country resulted in the deaths of at least 39 people, the election has been described as free and fair in most places. In Kano state, the most populous state in northern Nigeria and often a volatile place during elections, they were described as free, fair and peaceful for the first time since 1999. In addition, there are two major indications that the elections were largely credible. First, the outcome of the elections for several key individuals in the country such as incumbent governors, former governors and astute politicians points to the fact that the will of the people prevailed in places. For instance, the incumbent senate president, Dr Bukola Saraki, two sitting governors and six former governors lost to relatively unknown candidates. These incumbents were previously thought of as “untouchables” and supposedly had guaranteed senate seats.

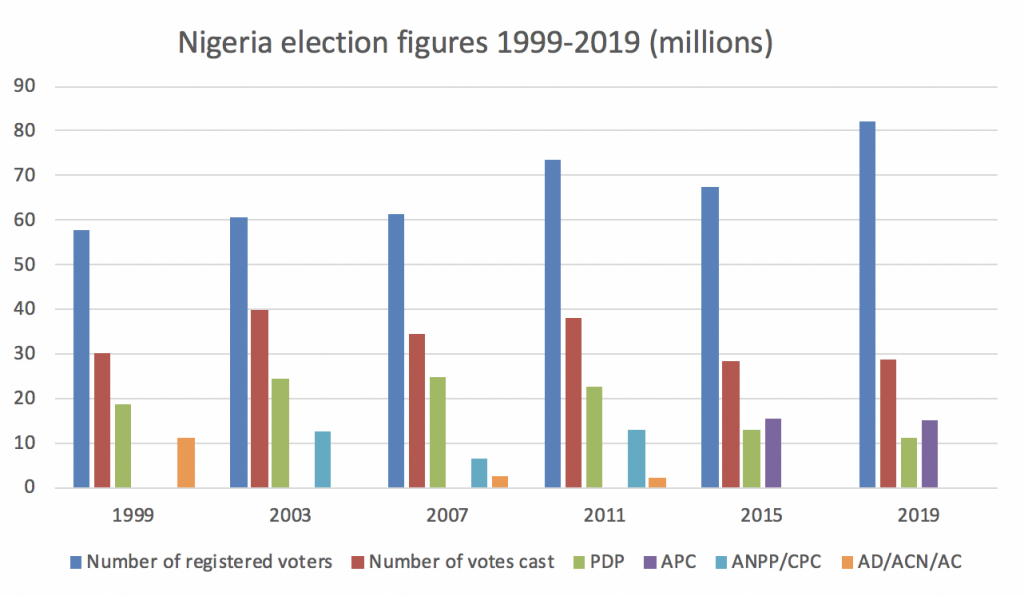

Second, the use of electronic card readers reduced the incidence of electoral manipulation that had characterised previous elections. The card readers were first used in the 2015 elections and the technology had been improved upon in 2019. The infographic above shows the difference between registered voters and votes cast in Nigerian elections since 1999. Prior to the introduction of the card readers, there was a higher proportion of votes cast per number of registered voters. This is because elections were fraught with irregularities and manipulations. The lower proportion of votes cast in the last two elections indicates the use of electronic card readers has limited the incidence of multiple and underage voting. Despite a record number of registered voters in 2019, the voter turnout was a record low of 35.6% – indicating electronic voting has reduced electoral manipulations and making the elections more credible.

While the 2019 presidential election was not perfect, there are indications that democracy is gradually being entrenched in Nigeria. It is now hoped that the re-election of Buhari will encourage further cooperation between Nigeria and its neighbours in the fight against Boko Haram and its affiliates in West Africa.

Dr Olayinka Ajala holds a doctorate degree in Politics from the University of York and a Masters degree in Globalisation and Development from the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex. In 2014, Olayinka was a visiting fellow/lecturer at the Combating Terrorism Centre, United States Military Academy, West Point. He also consults for local and international organisations including the European Union and Ministry of Defence, UK.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.