World Anti-Corruption Day: The Implications for Australia

As Parliament debates a national integrity commission, two thirds of Australians want an anti-corruption watchdog.

As we celebrate World Anti-Corruption Day on the 9 December, its timely to remember the impact that bribery and corruption has on people, society and democracy. Transparency International defines corruption broadly as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain”. For those who report on corruption and hold governments and the private sector to account, it can be a deadly business.

Corruption can cost people their freedom, health and money. It depletes national wealth, leads to environmental degradation and corrodes the social fabric of society. Corruption undermines people’s trust in the political system, in its institutions and its leadership.

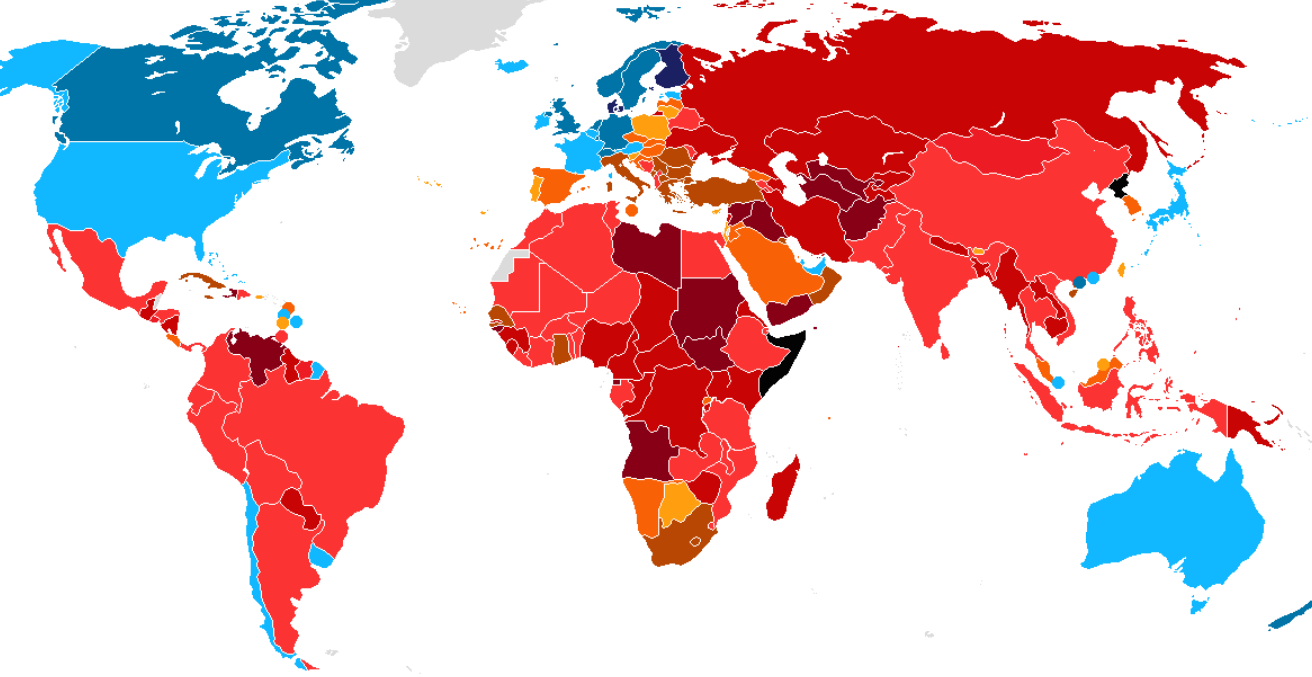

The past 12 months in Australia have seen trust and confidence in government slip to an all-time low. This is hardly surprising. The 2017 Corruption Perception Index saw Australia continue its downward slide, slipping eight points in six years, and putting it outside the position it once held in the top 10 countries.

The 2018 Global Corruption Barometer survey confirmed that 85% of Australians think some federal politicians are corrupt and 56% said they had personally witnessed or suspected favoritism by politicians or elected officials in exchange for donations or support.

Undue influence and decisions that benefit business and powerful individuals are real and driving corruption concerns in Australia. Industry influence in the resource sector in Australia, particularly with regard to large infrastructure projects in Western Australia and Queensland, can interfere with both the policy and political agenda of government in the development of major resource projects.

Corruption can be clear cut and criminal, but at other times it’s not a crime, rather the grey area of integrity failings and misconduct. This can be equally as corrosive and result in decisions not made in the public interest.

There have been well-documented corruption and crime investigations in Australia that have involved the investigation of politicians with close ties to industry for corruptly influencing the mining approvals process. Inadequate regulation of political donations and lobbyists, the movement of staff between government and industry and the “culture of mateship” in the mining sector in Australia, can allow inappropriate influence to occur. At worst, a bad decision is rooted in corruption, at best, a lack of integrity. It helps explain why two thirds of Australians want a national anti-corruption watchdog.

Australia’s current anti-corruption regime is not fit for purpose. There are too many gaps, poor coordination and a lack of resources across the government agencies to tackle corruption effectively. Much needs to be done to shine a light on deals in the dark, dirty money and unethical behaviour.

The corrupt don’t like paper trails, they like secrecy. What better way to hide corrupt activity than with a secret company or trust as a front? You can anonymously open bank accounts, make transfers and launder dirty money. Knowing who the real beneficial owner of a company is helps to combat corruption and detect the proceeds of crime being laundered.

Australia has become a “go to” destination for money laundering through the property market. Transparency International’s report, Doors Wide Open, makes it clear that a public register of beneficial ownership would help tackle rampant money laundering through the property market. The purchase of real estate with funds from suspicious sources and through trusts and shell companies is just all too easy in Australia.

Companies can and do act as attractive “get away cars” to launder the proceeds of crime, corruption, tax evasion and illicit financial flows, washing the funds clean before they enter the financial system. This is made easier and less risky for individuals if the beneficial ownership of these companies remains unknown.

Australia, like the majority of G20 countries, still does not know who owns and controls shell companies and trusts in its territories because of inadequate beneficial ownership legal frameworks. Publicly-available central registers where the details of every beneficial owner of every company are stored would help gather this information. Only six G20 countries now have central registers, and only the UK’s is publicly available.

Despite all the talk about terrorism and security, we face another challenge. The Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 – which aims to bring Australia into line with international best practice to deter money laundering and terrorism financing – is not broad enough in scope. While it covers the financial sector, gambling sector, bullion dealers and other professionals, it does not cover real estate agents, accountants and lawyers: the very people that facilitate the purchase and sale of property.

This is why Australia needs a National Integrity Commission: an independent broad-based agency that provides a comprehensive and coordinated approach to tackling corruption. The Bill introduced to the Australian Parliament on 26 November proposes a smart mix of prevention and enforcement. It promises to better address national as well as international corruption issues, such as money laundering, foreign bribery and responsible business conduct. Importantly, it recommends better support and protection for whistleblowers; this is long overdue in Australia.

A National Integrity Commission would keep watch over federal politicians and public servants. It would ensure they maintain the high levels of integrity the public expects of them. It would protect the public funds that we entrust them to use in the national interest.

The stalling by some in the Australian government is hard to understand: after all, what government would not want to tackle corruption effectively? With a federal election just around the corner, politicians who ignore what the public wants and expects – improved transparency and accountability – do so at their peril.

They say “sunlight is the best form of disinfectant” and transparency is the surest way of guarding against corruption. Transparency helps increase trust in the people and institutions on which our futures depend. We need to be united against corruption.

Serena Lillywhite is the CEO of Transparency International Australia.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.