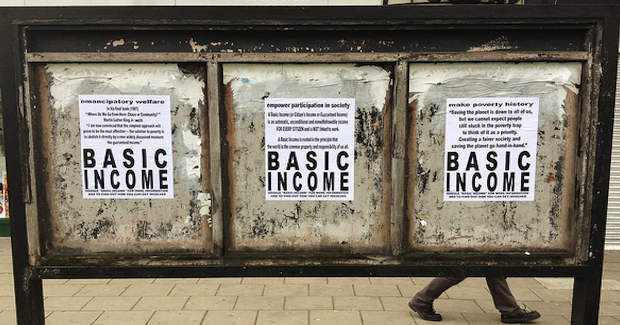

Time for a Universal Basic Income?

The concept of a universal basic income has received renewed attention in 2016. The general frustration with mainstream politics and the finance sector—manifested in the Brexit and US election votes—is indicative of the view that the economic system in the West is deficient. Inequality is growing, welfare costs are increasing, and technological disruption is escalating; prompting some to warm to the idea of a guaranteed basic income for everyone.

The technological revolution and the resulting digital economy are driving the increasing interest in the Universal Basic Income (UBI). The fourth industrial revolution, as the World Economic Forum (WEF) calls it, is convulsing labour markets worldwide. There is growing evidence that with automation and artificial intelligence, more and more jobs will be taken over within the coming decade by computers and machines.

Complex social benefits

Social benefit systems encompass the programs, laws, and services that address social needs regarded as essential to the well-being of a society. If well designed, targeted, and not abused, they lift people out of poverty and tackle inequality, which is key for social cohesion. They are also inevitably complex and bureaucratic. Income-related benefits aimed at reducing poverty may simultaneously diminish incentives to work if not well targeted. Contingent benefits target causes of poverty like old age, unemployment, disability and large or broken families. These may be costly and subject to illegal abuse, which is a great burden to the economic health of any society. Basic income proposals seek to simplify those expenses by doing away with complex benefit systems.

Conflicting arguments

The concept of a universal basic income attracts people from both ends of the political spectrum as it reduces government’s social obligations to a minimum. The right tends to be open to it, especially the libertarian right, while left-wingers appreciate it because it offers a simple and comprehensive answer to concerns of inequity and, potentially, a way to liberate workers from low-skill jobs.

UBI advocates claim it will help society survive technology-induced mass unemployment, and will cure us of extreme poverty and wealth inequality by providing a safety net. Their theory is that a UBI will free up potential entrepreneurs and creative people to take risks chasing their ideas—something difficult to commit to if the probable downside are bankruptcy and homelessness. The belief is that automation will make human labour so worthless, and humanity so fantastically wealthy, that a free monthly amount of money will benefit, not harm, the economy. A UBI could ensure a more equal division of the benefits of the technological revolution and continue to drive demand.

Gaining momentum?

In Finland, the government has pushing ahead with a trial to give basic income to about 2,000 people from low-income groups. This pilot project would provide €560 (A$789) each month to each individual. The Netherlands is also launching a UBI trial to start in the city of Utrecht in 2017.

However, critics of a UBI say that disconnecting the link between work done and money earned would be bad for society and that a basic income cannot be a substitute for a well-designed welfare system. Moreover, opponents of the measure contend that it is a Marxist dream with sky-high costs that will create economic chaos, and is fiscally not feasible. Additionally, the prospect of one country offering UBI to its citizens would create a seismic and unsustainable migration movement.

Furthermore, the renewed interest in UBI has prompted some governments to refer the issue to a referendum, as Switzerland did on 5 June this year. Close to 80 per cent of voters opposed the plan. Opponents of UBI in the country warned that given Switzerland’s high living standard, millions of people would try to move into the country. Some politicians described it as a hand grenade that would threaten to tear the whole system to pieces and is the most dangerous and harmful initiative that has ever been submitted.

Despite the result, the referendum is a signal that the debate has gained some life. Some argue that a UBI is an impossible and harmful measure. Others describe it as the solution to coming anaemic economic growth and technological unemployment challenges, thus, a simply inevitable government policy. It is hard to say who is right, given that it is a discussion based on uncertainty.

Is UBI the future of welfare? Perhaps. But if so, that future is a distant prospect. Currently, the expenditure associated with UBI is too high. There is a lot of division about the appropriate social and political response, and a lack of consensus about how it could be implemented and funded. In the context of contemporary labour instability, the referendum called in Switzerland—one of the world’s most prosperous countries—and the Finnish trial proposal are both important testaments to UBI’s progress into the mainstream, if not its immediate viability.

Pedro Sousa is a political economist who has worked at the OECD and the UN. He is the co-founder of Paris-based community based think tank ECON+.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.