Japan’s Evolving Defence Posture

Japan is debating formal revision of its ‘Peace Constitution’. Recent legal reinterpretations and new security laws allow the Japanese Self-Defence Forces to do more abroad than at any time since World War II. Further adjustment to military roles and capabilities will have implications for East Asian security. So, in what ways is Japan’s defence posture changing and what can be inferred from its historical trajectory?

Japan’s defence posture has gradually but markedly evolved since the end of the US occupation in 1952. With the dispatch of Self-Defense Forces (SDF) to Iraq in 2004, Japanese troops were deployed to a country with ongoing combat for the first time since World War II. Japan’s active participation in the US war against terrorism stood in stark contrast to Tokyo’s ‘chequebook diplomacy’ during the 1991 Gulf War.

After the July 2013 Upper House elections resulted in the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) regaining control of both legislative chambers, political leaders who had long advocated revising Japan’s pacifist constitution charted an increasingly robust defence posture vis-à-vis North Korea and China.

A July 2014 Cabinet decision offered a constitutional reinterpretation towards exercising collective self-defence and expanding the geographic and situational limits of SDF operations. Japan’s Diet (Parliament) passed implementing legislation in September 2015 over protests which alleged that Tokyo was abandoning its postwar pacifism. Meanwhile, Japan continues to deepen security cooperation with the US, Australia, and partners in Southeast Asia and beyond.

In light of these developments, is Japan’s defence posture departing from its post-war trajectory?

Charting defence-posture trajectories

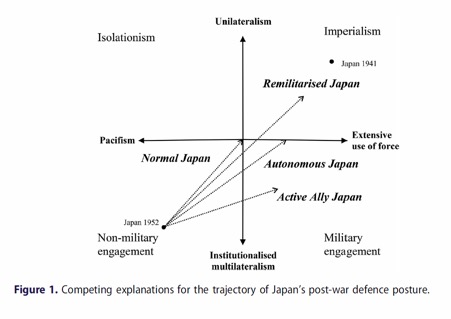

In order to make the concept of defence posture manageable, while keeping its representation realistic enough to consider change over time, this article illustrates Japan’s defence posture in a two-dimensional space defined by its military orientation (from pacifism to extensive uses of force) and international orientation (from institutionalised multilateralism to unilateralism). The four quadrants in Figure 1 correspond to four general types of defence posture, each associated with certain strategic priorities, methods for pursuing security, and ways of relating to the international system. With this framework, it is possible to chart trends in defence posture, where change is guided by a government’s efforts to derive the greatest benefits from the international environment under existing domestic political constraints.

Active Ally Japan is the case made by influential US defence specialists who want to see a more assertive Japan that takes on greater responsibility in international security affairs while remaining firmly tied to its security relationship with the US.

Autonomous Japan is the trajectory advocated by Japanese conservative nationalists who want the military to play a larger role while the nation assumes greater independence from US foreign policy, as well as multilateral constraints.

Remilitarised Japan is what Japanese progressives and critics in neighbouring countries claim is a return to an aggressive defence posture that sheds Japan’s post-war pacifism and forsakes multilateralism.

A fourth trajectory, which is less militaristic and unilateral than these critics fear, is represented by Normal Japan. The goal of a normalisation strategy is to achieve a balance between non-military and military means, and between unilateral and multilateral approaches.

A detailed analysis of Japan’s evolving post-war defence posture suggests that Tokyo is following a Normal Japan trajectory in service of national strategic interests.

The evolution of Japan’s defence posture

Return to defence (1952–89)

After World War II, Japan was disarmed under the US-led occupation and adopted its current ‘Peace Constitution’ in 1946. Japan’s dramatic shift in defence posture from unilateral uses of force to multilateral pacifism (from the upper right to the lower left of Figure 1) was imposed with its loss in the war and was firmly institutionalised by the time Japan signed the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1951. Out of these circumstances, Japan’s defence posture became defined by the Yoshida Doctrine—a strategy of aligning with the US on international issues, maintaining minimum military capabilities, reassuring regional neighbours and focusing on economic recovery.

Japan’s postwar economic miracle made it a financial superpower and one of the world’s richest states. Along the way, the SDF gradually expanded its capabilities and assumed primary responsibility for conventional national defence. Japan’s defence posture remained multilateral and pacifist, but had clearly begun to move from its early postwar position (away from the lower left of Figure 1 towards the centre).

Strategic adjustment (1989–2001)

The 1990s are often referred to as Japan’s ‘lost decade’ because of the economy’s protracted recession, from the bursting of the economic bubble in 1990 through the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis of 1997. But the decade also included landmark adjustments in Japan’s defence posture. The dissolution of the Soviet threat in the early 1990s reshaped Japan’s strategic landscape. In the late 1990s, the necessity of being able to respond to regional contingencies moved Japan’s defence posture further away from staunch pacifism and strict multilateralism, while still remaining in the lower-left quadrant of Figure 1.

A more proactive Japan? (2001–08)

The 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks and US war on terrorism challenged the Japanese people to re-examine how they perceived threats and pursued security. Public memory of World War II was fading and concern over North Korea was growing. The socialist opposition in the Diet had all but disintegrated and a new generation of ‘realist’ Japanese politicians came to power.

The DPJ interlude (2009–12)

With a resounding victory in the 30 August 2009 legislative elections, the DPJ took control of government for the first time, promising a new course in security policy. Once in office, however, the DPJ continued incremental adjustments along a Normal Japan trajectory, despite at times encouraging pacifist or isolationist supporters and straining alliance cooperation with the US. Instead of revolutionising security policy, DPJ governments were focused on responding to crises. The DPJ faced its greatest crisis following the 11 March 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, including the nuclear meltdowns at Fukushima. Operation Tomodachi, the successful Japan–US relief effort in the aftermath of the disaster, elevated public opinion of the SDF and the alliance.

The LDP is back: Whither Japan? (2013– )

With the December 2012 elections, the LDP regained power with an overwhelming majority in the legislature. The recent Japanese policy change garnering most public attention was the July 2014 Cabinet decision reinterpreting Article 9 for exercising collective self-defence, and the decision’s implementing legislation. Japanese strategists argue that such changes in defence posture will allow Japan to help build a regional security network in Asia and respond with partners to emergencies without significant legislative delay.

Explaining Japan’s strategic trajectory

Japan’s postwar defence posture has been consistently more pacifist than militaristic, with policy changes that are focused on defence and deterrence. Analysis of postwar changes in Japan’s defence posture strongly suggests that Tokyo is not pursuing an Autonomous Japan strategy. Evidence also suggests that Tokyo is not charting the trajectory of an Active Ally. Japan’s security policy has not integrated as much with other US allies—notably South Korea— as would be expected from an Active Ally strategy. While Japan’s defence posture is less multilateral than during the Cold War in the sense that it is less reliant on the UN for taking actions relevant to international security, Tokyo has not shown signs of crossing the horizontal axis in Figure 1 to pursue a Remilitarised Japan trajectory.

Instead, the evolution observed in Japan’s defence posture has exhibited three basic characteristics consistent with a Normal Japan trajectory: incremental change, a tendency towards the centre of Figure 1, and a commitment to multilateralism.

Conclusion

Japan’s long-term strategic planning will continue to pay close attention to the challenges posed by China’s rising power and influence. Policymakers in Tokyo will evaluate the costs and benefits of various security initiatives while looking to keep the US’s strategy in Asia anchored in Japan. Japan’s defence posture will remain multilateral, and Tokyo will continue to rely on Washington for power-projection capabilities and a nuclear deterrent rather than develop its own.

Japan is moving away from its postwar pacifism by becoming more involved in maritime security efforts, aiding UN peacekeeping missions, employing military assets in disaster response, dealing firmly with North Korea, and displaying a visible ‘hedge’ vis-à-vis China. This bodes well for Japan’s international security role and for peace and stability in East Asia.

If Japanese leaders better manage historical controversies, and policymakers in neighbouring countries recognise the above body of evidence concerning doctrine and capabilities, all parties can be reassured that worst-case assumptions about the trajectory of Japan’s defence posture are unwarranted.

Leif-Eric Easley is assistant professor of international studies at Ewha University and a research fellow at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

This article is an extract from Easley’s article in Volume 71, Issue 1 of the Australian Journal of International Affairs titled ‘How proactive? How pacifist? Charting Japan’s evolving defence posture‘. It is republished with permission.