Time Ticks Closer to Nuclear Midnight

This week’s false ballistic missile warning in Hawaii gave the world its first glance of what the first 38 minutes of nuclear war might feel like as political tensions turned to real-life panic. As time ticks away, can catastrophe be averted?

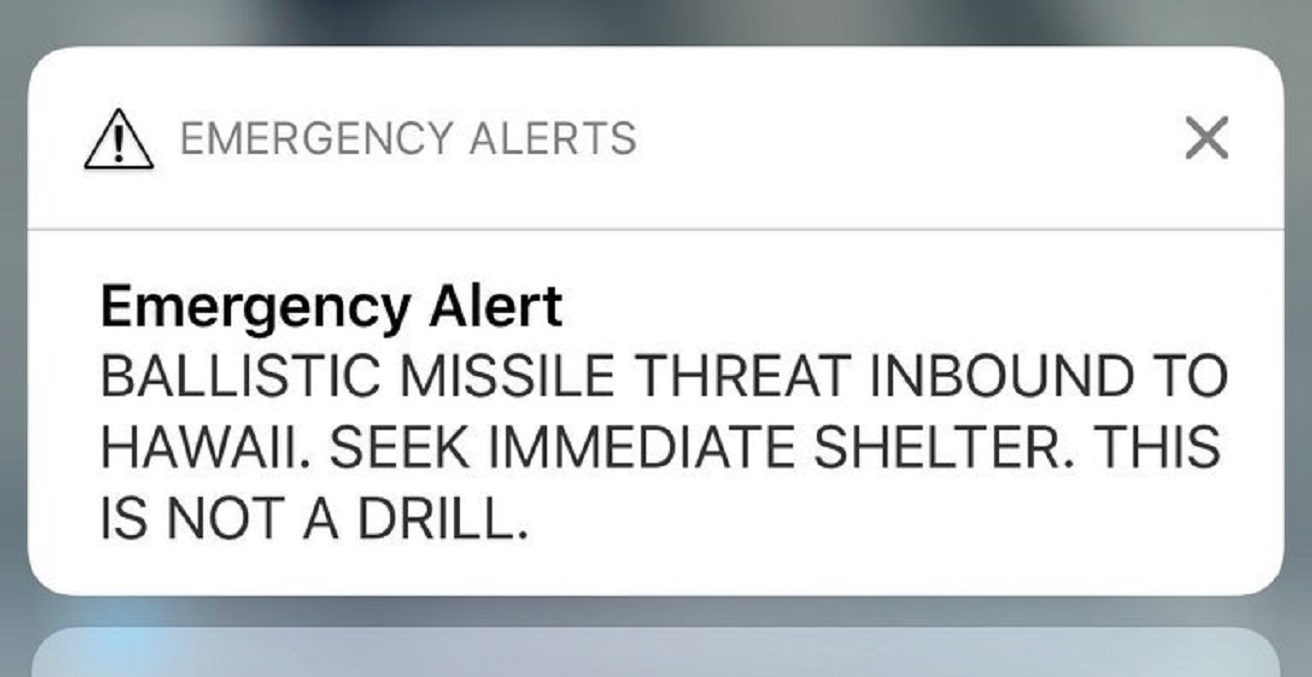

On 13 January an emergency alarm was sent via mobile phones to residents of Hawaii asking them to evacuate to designated assembly points because of a ballistic missile attack. Not surprisingly, the early morning alert sent by the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency caused panic in the populace. It took authorities 38 minutes to correct that advisory with a statement saying it was a false alarm: an employee had pushed the wrong button. Officials have been struggling since then to explain the confusion over how the mistaken alert was issued and why it took so long to be rescinded. The ensuing speculation among experts has focussed on how the incident highlights the heightened and growing risks of an unintended nuclear war with North Korea.

What if instead we are at the point where two patterns of statements and incidents are about to intersect? If so, we may be on the cusp of a second Korean war, except this time it might escalate above the nuclear threshold.

On the one hand, we have had a “pattern of comments that indicate a preference for a military response to North Korea“. Since that caution by David Graham writing in The Atlantic in October, we have had the surreal boast from President Donald Trump that his nuclear button is bigger and works better than Kim Jong-un’s. In the final quarter of last year, North Korea’s weaponised intercontinental nuclear capability prompted President Trump to mock President Kim as a “Rocket Man… on a suicide mission for himself and for his regime”. In response Kim derided Trump as “a mentally deranged dotard“, while Russia’s foreign minister Sergei Lavrov called for calm in this “kindergarten fight between children“.

On the other hand, the pattern of bellicose statements by President Trump and his senior advisers, that has already unnerved South Koreans, is reflected in an emerging pattern of false alarms on evacuation. They provide a worrying backdrop to the most recent incident in Hawaii.

On 3 September 2017, North Korea conducted its sixth and largest nuclear test, with the yield estimated to be in the 160kt range. (The Hiroshima bomb was about 15kt.) In the midst of the heightened tension, on 23 September an alert was issued via mobile phones and social media advising US military personnel and their families to evacuate the Korean Peninsula. Two days later, the US military said it had opened an investigation into the ‘fake’ mobile phone alerts and social media messages. US Forces Korea posted an official statement on its Facebook page instructing all US military and defence personnel to confirm the authenticity of any evacuation orders before acting on them. The incident quickly disappeared from public consciousness as a hoax.

Pyongyang also carried out 16 missile tests last year. On 29 November, it conducted its longest range intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) test that showcased its ability to launch a Hwasong-15 ICBM with a 13,000km range. Although the missile likely carried only a mock warhead (to increase the range) believed to have broken up on re-entering the atmosphere, it did put Washington DC within range of North Korean nuclear bombs.

Speaking at the Reagan National Defense Forum in Simi Valley, California on 3 December, National Security Adviser General H. R. McMaster said the threat of a war with North Korea was growing daily. On 4 December, Republican senator Lindsey Graham, a member of the Senate armed services committee, called on the Pentagon to move the families of US military personnel out of South Korea.

Forgive me for being a cynic, but now consider the following. If the US military is preparing for the contingency of a strike on North Korea, including targeted strikes intended to send a message of resolve by causing a ‘bloody nose’ rather than taking out all nuclear assets, planners must factor in some risk of a retaliatory attack by North Korea. No US military planner can be confident of taking out 100 per cent of North Korean nuclear assets in a surprise military strike. US personnel in the Korean Peninsula and residents of Hawaii would be on the front and second lines of any North Korean attacks. (It’s unclear how much room Trump’s America First policy leaves for considering South Korean and Japanese lives in the calculation.)

Evacuation drills, no matter how scrupulously conducted, cannot simulate an actual alarm advising evacuation. But the only way to do this is to issue an alert, test the response, then issue a correction in short order saying the alert was a false alarm and reassuring everyone that all is in order. A secondary benefit of such a deliberately staged false exercise is it might sow confusion among North Korean ‘first responders’ to a real US attack later, when even a few minutes of extra time gained could make a substantial difference to the North Korean capability to launch a counter-attack.

Meanwhile a group of 17 former nuclear launch control officers has issued a statement expressing intensified alarm at President Trump’s fitness to serve as the US commander-in-chief, his inflammatory rhetoric and propensity to brandish nuclear threats and the lack of reliable safeguards against his absolute authority to order the first use of nuclear weapons.

In almost all cases, the cock-up theory provides the better explanation of messed up events than a conspiracy theory. The worrying thought is that ‘in almost all cases’ does not translate into ‘in every single instance’. In that context, one final indicator. The New York Times reported on 14 January that the US military is indeed quietly preparing for a war with North Korea while hoping it will not happen.

The alternative of course is indeed the more reliable cock-up theory, especially as history is full of previous nuclear close calls. But then the added anxiety is the realisation that jittery fingers and nerves on edge dramatically increase the chances of a catastrophic mistake during tense crises and nuclear postures like hair-trigger alerts and launch-on-warning. It would help if the nuclear doomsday clock were to be wound back, but don’t hold your breath.

Professor Ramesh Thakur of the Australian National University is co-convenor of the Asia–Pacific Leadership Network on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament and author of Nuclear Weapons and International Security.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.