Charting Australia's Diplomatic Future

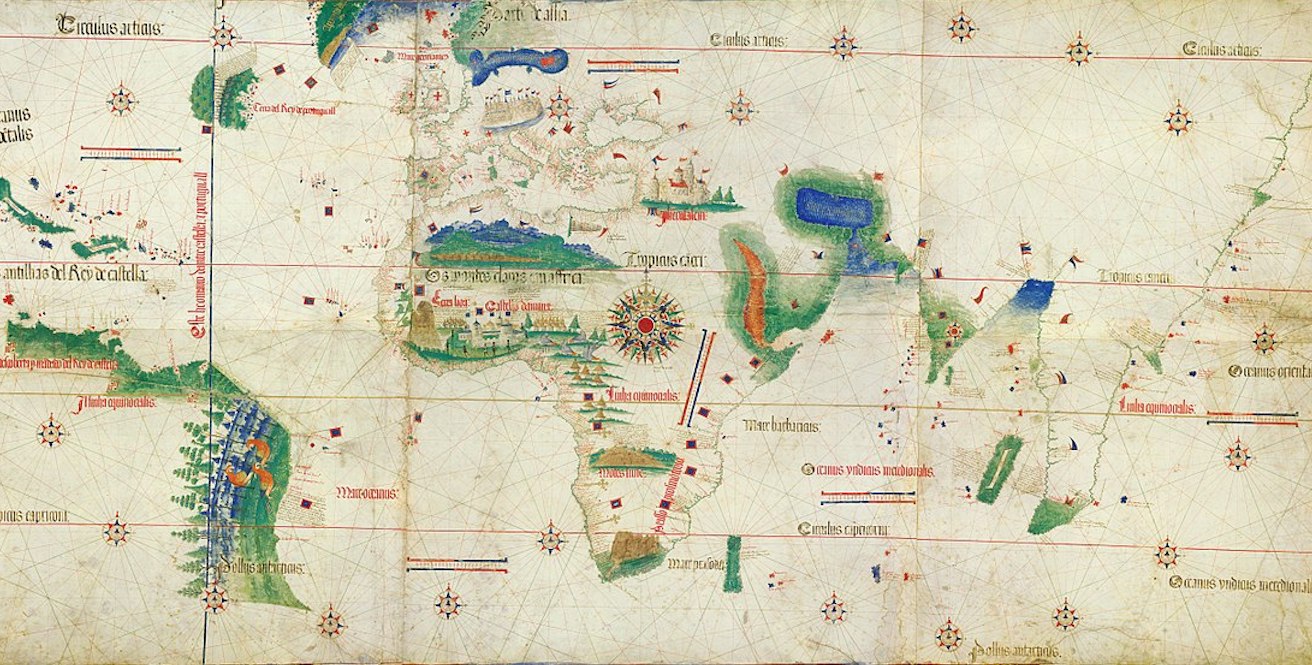

In a rapidly changing world, the unveiling of the Foreign Policy White Paper represents the closest thing the Turnbull government has to a map for navigating diplomatic contest, cooperation and opportunity.

True to good diplomatic form, there are no surprises in Australia’s latest Foreign Policy White Paper. It presents a realistic, comprehensive and at times, forensic view of the world that Australia confronts now and into the next decade.

Opportunity, security and strength are the framing themes of the white paper. Yet they offer rhetorical value only. Instead, underlying issues of contest and insecurity emerge as the dominant narrative, within which China is cast as the central antagonist. The phrase, “[t]oday China is challenging America’s position” sets the stage for the key moves that follow: centring on the US alliance and an Indo-Pacific strategic design, a commitment to the rules-based order, and a stepped-up focus on the South Pacific.

Overall, the white paper is a welcome contribution to Australia’s strategic policy landscape, providing a much-needed account of the security, economic and development dynamics that shape Australia’s foreign policy thinking.

What’s more, it’s been a long time coming for the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). Pushing back against enduring criticisms of short-termist, transactional, process-oriented thinking, it offers a strategic view where the big themes of power, interests, influence and values intersect, particularly in our own neighbourhood. This provides a necessary framework for DFAT, against which priorities might be set, resourced and, all going well, delivered.

The white paper plays heavily to the thought-leadership of former DFAT Secretary, Peter Varghese. In fact, bring together three recent speeches delivered by Varghese—An Australian Worldview: A Practitioner’s Perspective, Australian Diplomacy Today and more recently A Contested Asia: What Replaces US Strategic Predominance?– and you have, in broad terms, the framework and core themes of the white paper. Although, it must be said, it is presented somewhat less elegantly, and particularly when it comes to China, without the necessary nuance that characterises Varghese’s delivery.

Far from inspiring an upbeat confidence about Australia’s role in the world, the white paper forewarns a girding of the loins for what lies ahead.

Weighing in at 136 pages, there’s much to digest between its covers. No doubt foreign policy analysers, academics and commentators will be chewing over its contents for some time to come. From my early reading, four themes are deserving of attention:

- the Indo-Pacific

- Australian values

- active and determined diplomacy; and

- soft power.

The Indo-Pacific

Wasting no time on nostalgia for the past, the white paper casts Australia’s interests firmly in the Indo-Pacific.

No surprises there. This is the language advocated by DFAT and our Western Australian foreign minister for some time now; and it makes sense. The Indo-Pacific recognises “Australia’s distinctive geo-strategic position as a continent which faces two oceans.” It suggests a wider strategic heft and ties Australia’s interests to the key maritime concerns in the region.

But the language here raises some hackles across the region. Many of the ASEAN nations see it as diminishing, even dismissing, their relevance. For China, it signals a strategic design aimed at containment: a view reinforced by US President Donald Trump’s recent spruiking of the term. The optics here are problematic and will require careful explanation and management. In particular, attention should be given to assuring our neighbours and partners in the region that Australia’s view of the Indo-Pacific is an inclusive one.

Australian values

Australian values take centre stage within this Indo-Pacific context, providing the “foundation upon which we build our international engagement”. Spanning a commitment to individual freedoms, liberal democracy, the rule of law, equality and mutual respect, they “reflect who we are and how we approach the world”.

As the foundations of success, these values underpin an almost uncompromising commitment to the US alliance, other liberal democracies in the region and the rules-based order.

While some might question the accuracy or credibility of the values statement (thank goodness the marriage equality result came through as it did), it makes sense for such a statement to appear early on. It reflects Varghese’s long-standing view that foreign policy begins at home and “giving expression to our values should be seen as a natural part of our international relations”.

But there’s a certain rigidity in the white paper’s expression of Australian values. It’s not clear how Australia might navigate those complex policy areas where core values don’t align on certain issues, or where they stand in competition to key interests. These are the dilemmas that Australian diplomats will confront regularly in the Indo-Pacific, where difference and diversity are characteristic features of interaction. Achieving balance in the way we understand, articulate and apply our values and interests will be essential to effective diplomacy.

Active and determined diplomacy

Against this background, Australia lifts its ambition to that of a “regional power with global interests”. It’s a step up from the enduring middle-power cloak Australia has quite willingly worn for some decades. Even MIKTA, the recent reinvention and darling of Australia’s middle-power statecraft has been dropped, with the only mention of it appearing somewhat unnecessarily in the glossary of terms.

And how will this upgraded regional power ambition be realised? According to the white paper, through active, determined and robust Australian diplomacy. Such affirmation of the criticality of Australian diplomacy is hugely positive. But the white paper is silent on matters of resourcing, and for an agency that struggles to maintain, let alone expand its operating budget, DFAT’s ability to deliver will be seriously tested.

Partnerships and soft power

Partnerships and soft power addressed in the final chapter provide encouraging signs of a foreign policy that is open to evolution and innovation in practice. Incorporating new diplomatic actors—from cities to students and unconventional modes of engagement; from digital to science and sports diplomacy—this final chapter underscores the complexity of the contemporary diplomatic landscape. Australia will continue to gain critical relational value from many of the initiatives referenced, especially the New Colombo Plan, and their relevance to strategic foreign policy should not be understated.

However, DFAT’s enduring attachment to soft power as a strategic marketing and communications exercise is superficial and flawed. Its preoccupation with nation branding and rankings suggests that, at least for the moment, popularity matters. It’s a formula that doesn’t necessarily foster strong relationships, build trust or reflect credibility. This is particularly the case in a region where the binaries between hard and soft power, traditional and public diplomacy, foreign and domestic audiences are increasingly blurred.

What next?

Australia’s Foreign Policy White Paper is not an end in itself, but the beginning of a series of necessary conversations at home and abroad. For DFAT and other key agencies, the real challenge lies in delivery. There is much work ahead to shore up the necessary political will and budgetary support required to ensure that our policymakers and diplomats are appropriately equipped to navigate Australia’s path in a world that is less certain and more contested than ever before.

Caitlin Byrne is director of the Griffith Asia Institute. She is also a Faculty Fellow of the University of Southern California’s Centre for Public Diplomacy (CPD), and alumna of the Asialink Leaders Program 2016.

This article is published under Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.