Between Aspiration and Reality in Nuclear Disarmament

The recent awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize for nuclear non-proliferation work gives hope for progress on nuclear disarmament, but a close look at the world’s most important disarmament forum prompts only dismay.

This year has seen momentous steps towards longstanding aspirational disarmament goals with the decades-old ambition for a treaty banning nuclear weapons realised in July. The new treaty reflects the spirit of the sole binding multilateral commitment to disarmament, the 1968 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). The NPT obliges good faith negotiations towards nuclear disarmament and the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) advisory opinion confirmed this obligation.

Despite the good news, it’s still necessary to confront the known qualitative improvement programs of the nuclear-armed states and the significant transparency and verification problems in the growing arsenals of the non-NPT nuclear states (India, Israel, North Korea and Pakistan) as well as China. The US-India deal also demonstrated that states do not have to join the NPT to benefit from international nuclear cooperation.

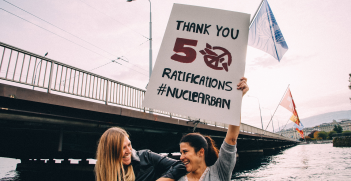

The resulting frustration of many non-nuclear states and civil society groups such as the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) has now found expression in the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty (NWBT). The NWBT opened for signature by the UN’s 193 member states in New York on 20 September 2017. Once ratified by 50 member states, the NWBT will enter into force after 90 days. It now has 53 signatories.

The July vote on the treaty, however, reflected profound divisions. States which had stayed away included the militarily more capable and ‘nuclear umbrella’ beneficiaries. A key problem with treaties such as the NWBT, which aim to create international norms, is the involvement of relevant users. For example, in the case of the 2008 Oslo Treaty the signatory states possess only an estimated 10 per cent of all cluster munitions worldwide. With non-participants, the US and Russia, accounting for over 90 per cent of nuclear warheads, the NWBT will face similar hurdles.

By contrast to the hopeful aspiration of the NWBT, the 2017 plenary session of the Geneva-based Conference on Disarmament (CD) provided an introduction to a more sobering version of nuclear disarmament efforts. The CD’s drama is illuminated by a series of towering monochrome grisaille murals completed by the Spanish artist José Maria Sert. These depict a hopeful journey from darkness to a brighter future and an end to war through cooperation and commitment to international law.

The CD itself is an expression of the post-war international order focused on ending the scourge of war, including nuclear disarmament. Accordingly, the CD is not only the international community’s most important disarmament platform but it also has the broadest relevant participation, including states such as India, North Korea and Pakistan, which are not members of the NPT. Nonetheless, the CD has been practically dysfunctional since the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty.

Paradoxically, it is the size and growth of the CD’s membership in past decades and therefore its very inclusiveness which appears to be the driver of its present difficulties. The membership’s growing size and complexity may have contributed to the reluctance of some the most powerful nations to subject their vital national security considerations to the uncertain fate of negotiations. This problem is compounded by the CD’s consensus rule, with unanimity the de facto standard in post-1945 UN instruments, which even UN officials now describe as a virtual veto. Such dynamics are uncomfortably reflected in the obvious absence of concessions on the conference floor and in the discreetly expressed disillusionment of UN and national officials. Other observers describe an eroding trust among states and a loss of political will to compromise.

The role of individual member states in this gridlock is also substantial. Many UN member states are unable to compromise on key issues, and commitments that states make have been described as having a very high ratio of rhetoric to facts. Even foundational UN charter norms, such as the obligation to settle disputes peacefully or the prohibition on threats of force, are commonly flouted.

As in other international legal matters, states naturally seek to maximise what they perceive as their national interest. This may include arguments that nuclear disarmament is a matter of national defence and security and as such falls exclusively within the domestic jurisdiction of states. Such an argument—as advanced by Pakistan in response to a recent case brought before the ICJ to force nuclear-armed states to pursue disarmament—may enable states to deflect disarmament efforts with the legal principle of the prohibition of intervention.

Today, major states largely accept nuclear-based deterrence in the absence of mainstream alternatives and in the context of low perceived risk. A nuclear balance has likely contributed to decades of declining conventional conflict. However, the possibility of nuclear conflict cannot be excluded. A number of ongoing flash points have potential nuclear dimensions, which raises the question of how humanity will fare in a future global conflict.

As archetypal Cold War warrior and former US Defense Secretary Robert McNamara noted, the risks of misinformation, miscalculation and misjudgement, and the possibility of a chain of events leading to nuclear war are real and substantial. The odds of catastrophic mishap will shorten further as new nuclear players without well-established safeguards, resources or expertise undertake the long journey along the nuclear learning curve. Inadequate nuclear disarmament endeavours are therefore only one of the reasons we have to be uneasy.

To a modern observer, the sad irony in Sert’s art is that it was completed only weeks before the outbreak of Spain’s own civil war which left half a million dead, and not long before another world war which ended the lives of tens of millions. And so, the backdrop to the international community’s most important (but effectively dysfunctional) disarmament forum is a reminder of our collective inability to know our future and, by extension, of the separation between hope and reality as they flow through the human story. Despite the NWBT’s aspirational effort, and a Nobel Peace Prize, there is little reason for optimism today.

Alexander Balas is a former investment manager at Invest Australia who has worked in various other roles across Australian government. He has travelled extensively through Asia and Europe, completed an MA in strategic and security studies at UNSW with a thesis focused on state-building and peacekeeping.

The views and opinions expressed are the author’s own and do not represent the views of any organisations the author is associated with.

This article has been published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.