Need for Improved EU-China Relations in the Belt and Road Era

Problems with projects such as the Belgrade-Budapest railroad show the need for better EU-China dialogue as the Belt and Road Initiative reaches into Europe.

As the terminal point of both the overland and the maritime routes envisioned within China’s action plan, the European Union faces significant geopolitical, economic and geostrategic consequences from the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The most evident influence will be on the sometimes cumbersome EU-China bilateral relations.

As the original focus of China’s action plan was on physical connectivity, the initial EU response to the BRI was a proposal, in 2015, to establish a policy forum—the EU-China Connectivity Platform—with the aim to promote cooperation on infrastructure, including financing, interoperability and logistics, and to achieve consistent objectives with its own infrastructure policy, the Trans European Network Transport (TEN-T).

Nevertheless, there is a growing sense of urgency to move forward to more substantive policy dialogues to create synergies between EU policies and projects and China’s BRI. At the Belt and Road Forum held in Beijing on 14-15 May 2017 European Commission Vice-President Jyrki Katainen set out the EU’s vision for improving Europe-Asia connectivity, which is a step forward in EU-China cooperation on a common policy objective. It confirms the EU’s willingness to “support cooperation with China on the BRI on the basis of China fulfilling its declared aim of making it an open initiative which adheres to market rules, EU and international requirements and standards, and complements EU policies and projects in order to deliver benefits for all parties concerned and in all the countries along the planned routes.”

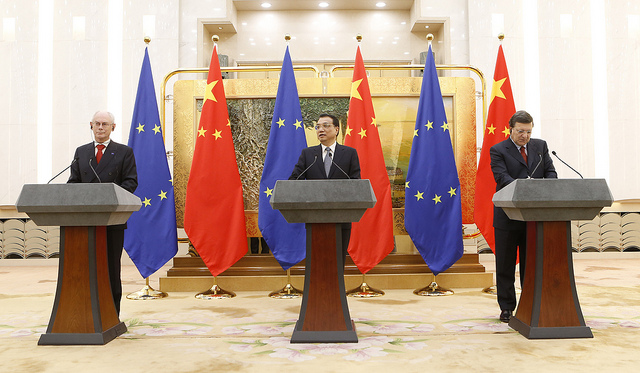

However, and not surprisingly, given the technical nature of the Connectivity Forum at the 19th EU-China Summit held in Brussels on 2 June, the progress acknowledged on “policy exchange and alignment on the principles and the priorities in fostering transport connections between the EU and China, based on the TEN-Ts framework and the Belt and Road Initiative, and involving relevant third countries”, in fact has boiled down to having agreed upon a list of infrastructural projects of common interest.

Within the current governance structure of EU-China relations, there is a need for matching the technical dialogue within the connectivity platform with a high-level policy dialogue on a broader range of issues. As the BRI goes far beyond physical connectivity to encompass a variety of policy areas, it has raised awareness of a need to give a boost to parallel dialogues on a large number of issues on which the EU and China have been handling meetings under the umbrella of the EU-China Summit since 1998, within more than 60 substantive and sectoral dialogues, including cooperation on climate, competition, customs, energy and investment.

Acknowledging the BRI as a simple “repackaging of the many initiatives and projects that China was already carrying out well before 2013″, it should today be widely accepted that none of its implications for the EU were in fact raised by the initiative itself. If an issue has been genuinely raised by the BRI, that issue is certainly the need to define a comprehensive response by the EU to the increasing Chinese influence in its territory as well as in neighbouring countries.

Such response should not be confined to just trade and investment issues, but should also encompass foreign policy, political and security issues in a comprehensive way. This is even more important, as the technical dialogues within the platform tend to cover only the new projects at the common borders between the TEN-T and the BRI, which are obviously located in member states at the southern and eastern borders of the EU. Instead, any other issue arising from infrastructure projects across non-EU member states or independent from the joint financing efforts envisaged for the projects included in the draft list is out of the scope of the platform, despite having potential implications on the smooth and efficient functioning of the overall European transport network.

The focus on improving infrastructure—the hardware of globalisation—lies behind an approach to regional integration that widely “differs from EU-style regionalism. Rather than using multilateral treaties to liberalise markets, China promises to facilitate prosperity by linking countries to its continuing growth through hard infrastructure such as railways, highways, ports, pipelines, industrial parks, border customs facilities, and special trade zones; and soft infrastructure such as development finance, trade and investment agreements, and multilateral cooperation forums.” Because truly multilateral cooperation fora and dialogues are missing, the building of new networks of physical infrastructure are somehow calling for the building of new fora of institutional infrastructure.

The need for improved institutional infrastructure has been increasingly apparent following the initial workings of the Connectivity Platform. Although discussions have not been confined to the coordination of infrastructure development plans in the EU and China, related issues such as market rules for public procurement and reciprocal access for investments in the respective markets have not yielded any substantive progress, which is hardly surprising given the political nature of those issues, which are supposed to be discussed at a policy, rather than a technical level.

Possibly the most evident case demonstrating the urgent need for an effective policy dialogue on the broad range of issues raised by the BRI, extending far beyond the practical aspects of infrastructure coordination, is the Belgrade-Budapest rail project. Regarded as a flagship project within the BRI, it is currently being reviewed by Brussels for potential infringements of the EU’s requirement that public tenders are offered for such large-scale infrastructure projects.

The case shows that the differing degrees of adherence to market rules in countries involved in the BRI is a source of inevitable frictions that can act as bottlenecks in the progress towards an effective transport network, and at the same time divert public opinion and policy dialogue away from substantive issues.

A further related issue that should deserve an effective dialogue is the financial viability of infrastructure projects along the BRI. The need to make the new transport routes (railways linking different cities in China to diverse European cities) attractive compared to the much cheaper seaborne trade has led Chinese authorities to subsidies firms with the aim to divert trade from sea to land. This approach acknowledges the need to reach a sufficient trade volume in order for the rail company to be profitable, while today the new transport routes are mainly working on the westbound direction, compared to the eastbound.

This practice, however, runs against the market rule principles prevailing in the EU, and therefore prevents mutual benefits for Chinese firms exporting to Europe, compared to European firms exporting to China as well as, in both cases, possibly also to other countries along the route. Enduring the lack of progress on a broad range of policy issues related to the BRI—mainly investment framework, market rules, market access and public procurement—avoids serious dialogue but paves the way to confrontational matters that may be even harder to handle.

Alessia Amighini is the senior associate research fellow at Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale (ISPI) and co-head of its Asia Program.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.